Exploring College Counseling Center Trends in Clients with Marginalized Gender Identities: Another View from Above

This blog post is dedicated in loving memory of Nora Maginnis (1963 to 2022). Nora, who served as a Psychiatric Nurse Practitioner at Penn State Counseling and Psychological Services, was a beloved colleague and trailblazer in providing affirming care for individuals who identify as transgender and non-binary. Nora, your tremendous work and impact will always be remembered.

Clinical research on individuals who identify as transgender and non-binary has shown disparities in mental health service utilization, presenting levels of distress, and treatment outcomes. While these discrepancies are most often interpreted through the lens of minority stress theories, individuals with trans and non-binary identities have also been shown to have unique resiliency and coping strategies, reflecting a strong and vibrant landscape of their diverse experiences.

Students who identify as transgender and non-binary can present to college counseling centers with unique backgrounds and needs, where access to care is more important than ever. The current blog marks a celebration of Transgender Awareness Week and a commemoration of the Transgender Day of Remembrance, which memorializes survivors and victims of transphobic violence. Accordingly, CCMH examined ten years of data to answer the following questions regarding TGNB+ (Transgender and Non-Binary, plus others) student clients who sought college counseling services:

- What are the trends in utilization at university and college counseling centers among TGNB+ clients?

- What are the concerns with which TGNB+ clients are presenting to treatment?

- How prevalent are experiences of discrimination and unfair treatment for TGNB+ clients at university and college counseling centers?

Increases in access to care for gender-diverse clients over the past decade

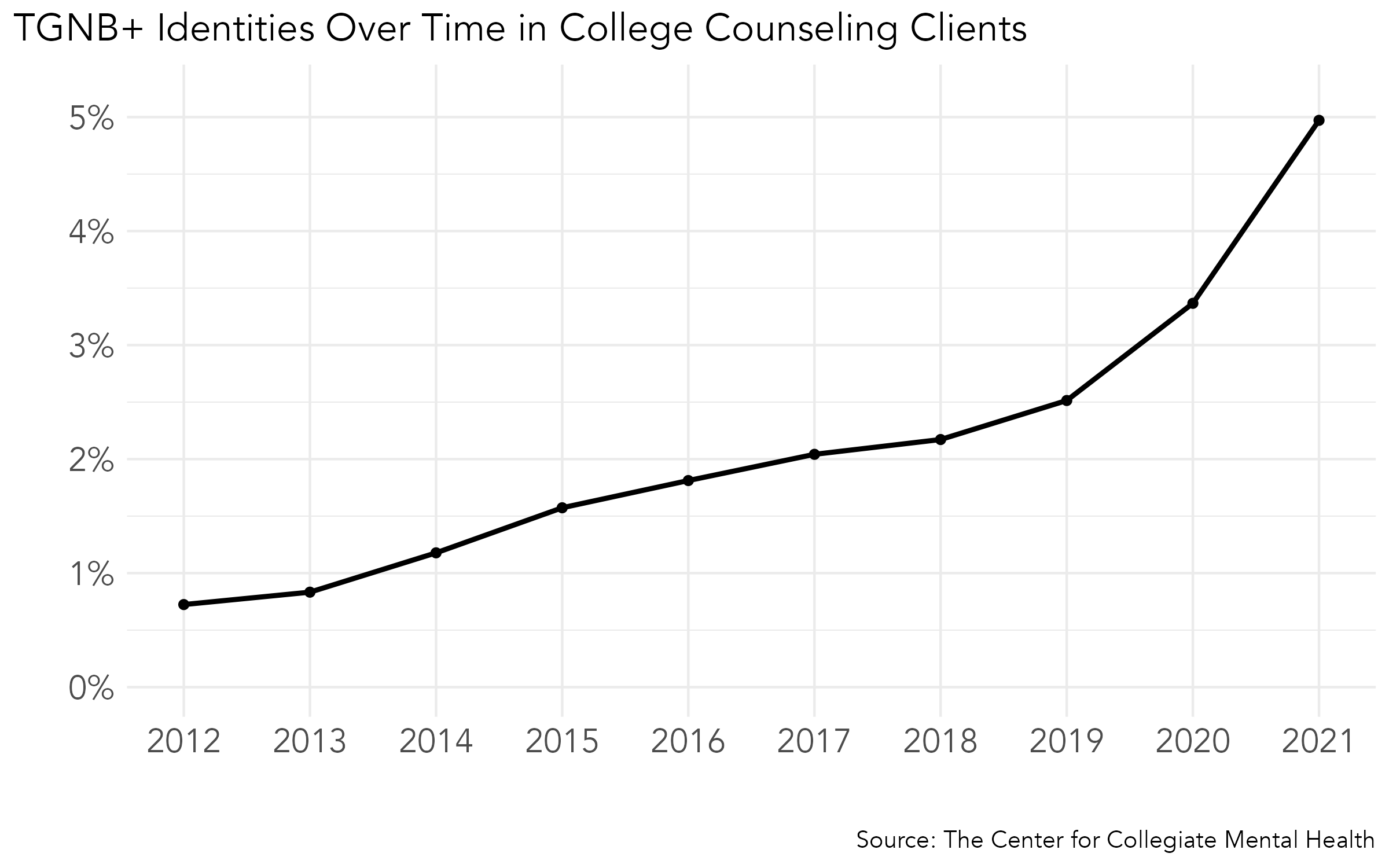

CCMH examined trends in gender diversity for students seeking college counseling services over the past decade. Overall, the proportion of total clients seeking services who identify as TGNB+ increased from 0.7% in the 2012-2013 academic year to 4.9% of clients in the 2021-2022.

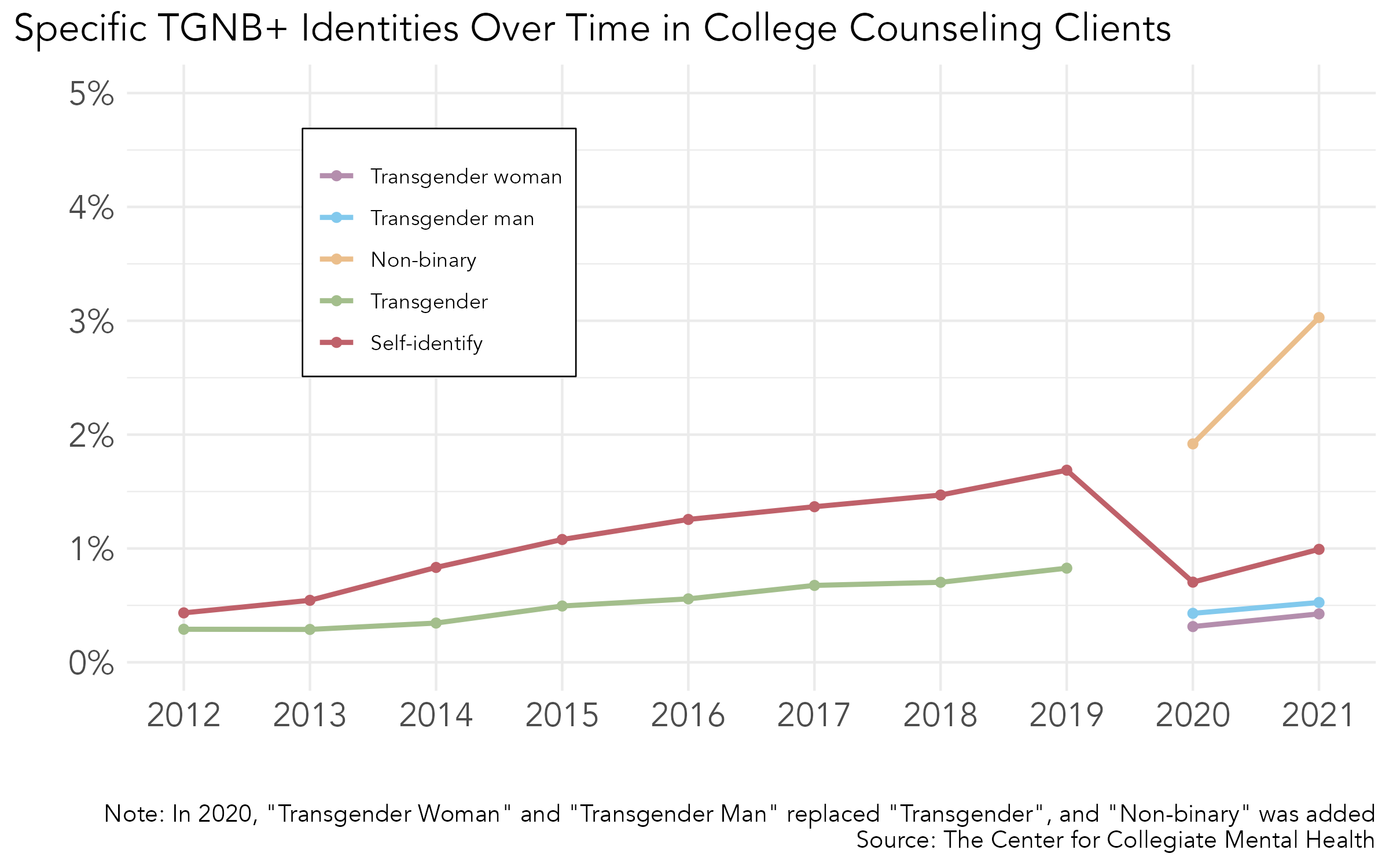

CCMH specifically examined the past two years of data, since gender identities of “transgender woman” and “transgender man” (previously just “transgender”), as well as “non-binary” were added as response options to the gender identity item in the CCMH Standardized Data Set materials in 2020. Overall, the frequency of student clients seeking services at counseling centers nationally who identified with diverse gender identities increased slightly over the past two years. Additionally, the percentage of clients choosing to “self-identify” their gender identity significantly declined from 1.7% in 2019-2020 to .7% in 2020-2021 and 1% respectively in 2021-2022, which convincingly demonstrates that the new gender identity response options added in 2020 better captured the identities of more students.

Collectively, these trends represent an increase in students with diverse gender identities receiving services, which might be a hopeful sign of improved access to and utilization of counseling services for these students over the past decade.

Presenting concerns and risk in gender-diverse student clients

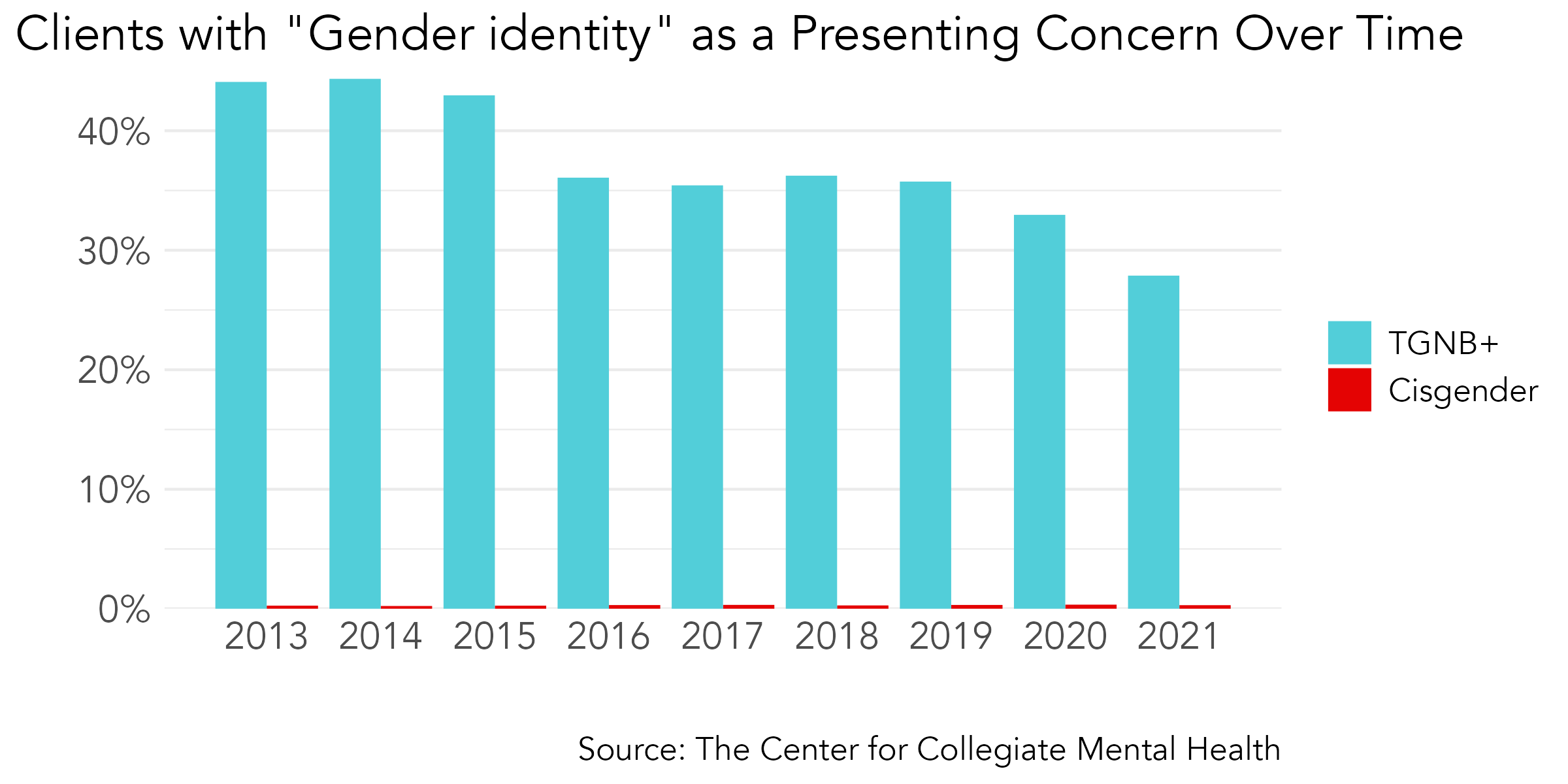

Clients with diverse gender identities commonly present to counseling centers with concerns related to their gender, and CCMH investigated if this has changed over time. The graph below shows the rates of “Gender identity” as a presenting concern for both TGNB+ and cisgender clients. The percentage of TGNB+ clients whose therapists identified “Gender identity” as a presenting concern have decreased over the past nine years, which might be an indication of more inclusive experiences in their everyday lives.

Check out this previous CCMH blog to see other presenting concerns for TGNB+ clients!

Discrimination and unfair treatment in gender-diverse student clients

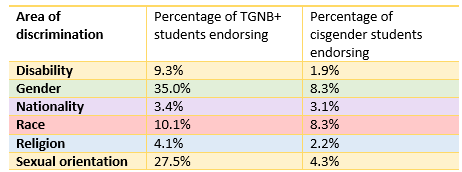

It is crucial for those working with students of marginalized gender identity to acknowledge a critical paradox – that even as “things seem to be getting better” with regard to increased acceptance and tolerance in the general public, students with marginalized gender identities seeking services are often at increased risk of adverse experiences, including experiences of discrimination (Russell & Fish, 2016). To further explore this set of experiences in a treatment-seeking population, CCMH implemented novel items on the SDS in 2021 capture the rate of “discrimination or unfair treatment due to any of the following parts of their identity” in the past six months: (1) disability; (2) gender; (3) nationality/county of origin; (4) race/ethnicity/culture; (5) religion; (6) and sexual orientation. We now report on the percentage of clients self-reporting any such experiences and if those rates fall along lines of marginalized gender identity.

Of all the student clients in the sample (n = 157,606):

- 9.7% self-reported discrimination due to gender identity

- Therapists of 1.8% reported that gender identity was a presenting concern

- Therapists of 1% reported that discrimination was a presenting concern

Of TGNB+ student clients (n = 2,027) in the sample:

- 45% self-reported discrimination based on at least one area of their identity

- 35% reported discrimination specifically based on their gender identity, compared to 8% of cisgender students

It is important to note that discrimination on the basis of gender is not an experience exclusive to TGNB+ individuals. This blogpost specifically focuses on trans and nonbinary individuals, but cisgender clients, particularly cisgender women, are also impacted by discrimination on the basis of gender.

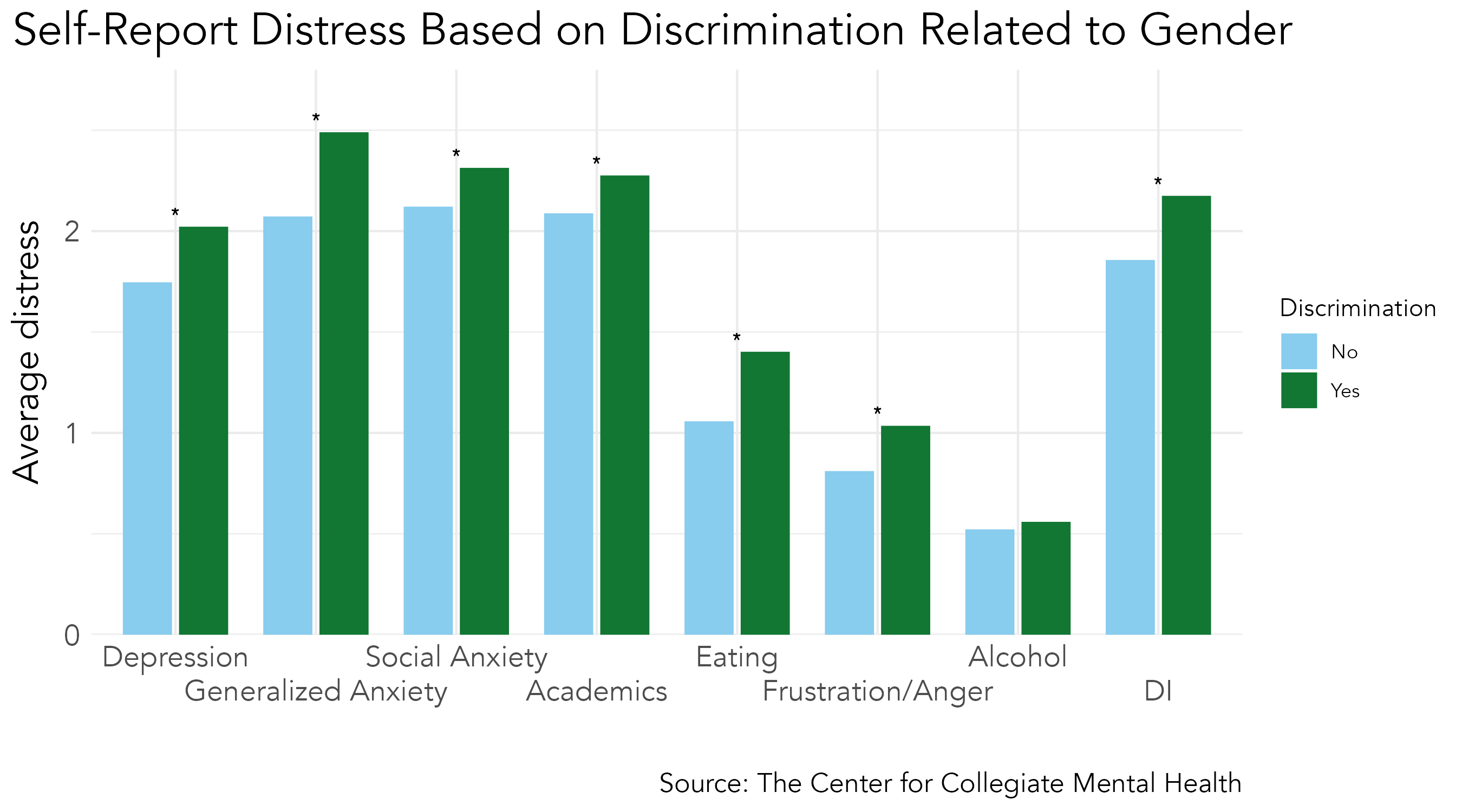

Experiences of discrimination or unfair treatment on the basis of gender identity is associated with increased levels of distress. Compared to students reporting no discrimination, those clients indicating discrimination pertaining to their gender identity were significantly more distressed in areas of Depression, Generalized Anxiety, Social Anxiety, Academics Concerns, Eating Concerns, Frustration/Anger, and overall distress. The asterisks represent significant differences.

It is important to acknowledge the impact of intersectional identities; that is, any one TGNB+ person’s experience is not only affected by gender identity, but also race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, and other identities that intersect with one other. For example, 24% of the TGNB+ students in the sample reported discrimination on the basis of both gender identity and one or more other identities. The table above shows percentages of TGNB+ student clients endorsing discrimination or unfair treatment on the basis of various identities.

Summary of findings

- Trends have shown an increase in proportion of TGNB+ students seeking counseling services nationally, which might be a hopeful sign of improved access to counseling services for these students over the past decade. In particular, there were notable increases in the percentage students with diverse gender identities who sought care after the onset of COVID-19, perhaps demonstrating how the widespread implementation of telehealth services improved access to care for these students.

- The percentage of students identifying as TGNB+ entering treatment with “Gender identity” as a concern has declined over the past nine years, which possibly might be an indication of more improved inclusive and experiences in their everyday lives

- A substantial portion (45%) of students identifying at TGNB+ report experiences of discrimination in the past 12 months. Clients who report discrimination based on their gender identity are significantly more distressed in numerous areas (Depression, Generalized Anxiety, Social Anxiety, Academics Concerns, Eating Concerns, Frustration/Anger, and overall distress) compared to clients reporting no discrimination. It is critical for therapists to recognize when TGNB+ share experiences of discrimination and how those are associated with increased distress.

CCMH continues to evolve its understanding and advocacy of all gender identities and strives to capture the experiences and concerns of this diverse group. While these findings might help us better understand the experiences of students with diverse gender identities and apparent gains in access to care, macro-level challenges persist as centers, institutions, and society are still rooted within a greater cisnormative systemic context.

This blog post was written by CCMH Business Team member, Katie Davis, M.S. Katie is a Doctoral Student in Clinical Psychology at PSU and a part of the Castonguay Lab.