Exploring the Relationship Between Client Risk Factors and Telehealth Services in College Counseling Centers

In March 2020, college counseling centers, along with many other healthcare facilities across the United States, encountered the unprecedented challenge of rapidly transitioning to tele-services in response to COVID-19. To accomplish this feat, counseling centers promptly transformed their in-person care to tele-services in a matter of days/weeks. While most college counseling centers continue to provide telehealth during the 2020-2021 academic year, many questions have emerged regarding the sustained utilization of tele-services within college counseling centers in the future. Some of the most common questions include: (a) will tele-services, at least in some capacity, become a permanent part of counseling center services?; (b) will some colleges/universities delegate a portion of traditional in-person counseling services to external telehealth vendors?; and (c) given tele-services are the most prominent current mode of treatment, what proportion of students seeking counseling center services possess risk factors that make them a poor fit for tele-services?

Regarding telehealth vendor utilization, it is important to recognize that while vendors are inclined to highlight their ability to connect students to services in a timely manner, they also tend to utilize a number of rule-out criteria to determine if a client is appropriate for telehealth services. These criteria are meant to identify students who represent risk that cannot be well managed via telehealth services and therefore need to be served using a different treatment approach such as in-person services at a counseling center. Below are some of the more common exclusionary criteria to establish if a client is an appropriate match for telehealth services:

- Current suicidal ideation

- Current thoughts of harming others

- Recent self-harm behavior

- Recent psychiatric hospitalization(s)

- Psychotic symptoms that are not stable

- Significant substance use problems

- Active high-risk Eating Disorder symptoms

- Active bipolar symptoms

- Recent significant medical issues

- Significant emotional regulation problems

To better understand the intersection of telehealth vendors within college/university settings, CCMH analyzed the prevalence of typical exclusionary criteria/risk factors within a large national sample of students seeking services at counseling centers. Additionally, CCMH evaluated whether the students who present with risk factors utilize more services than those who have no identified risk.

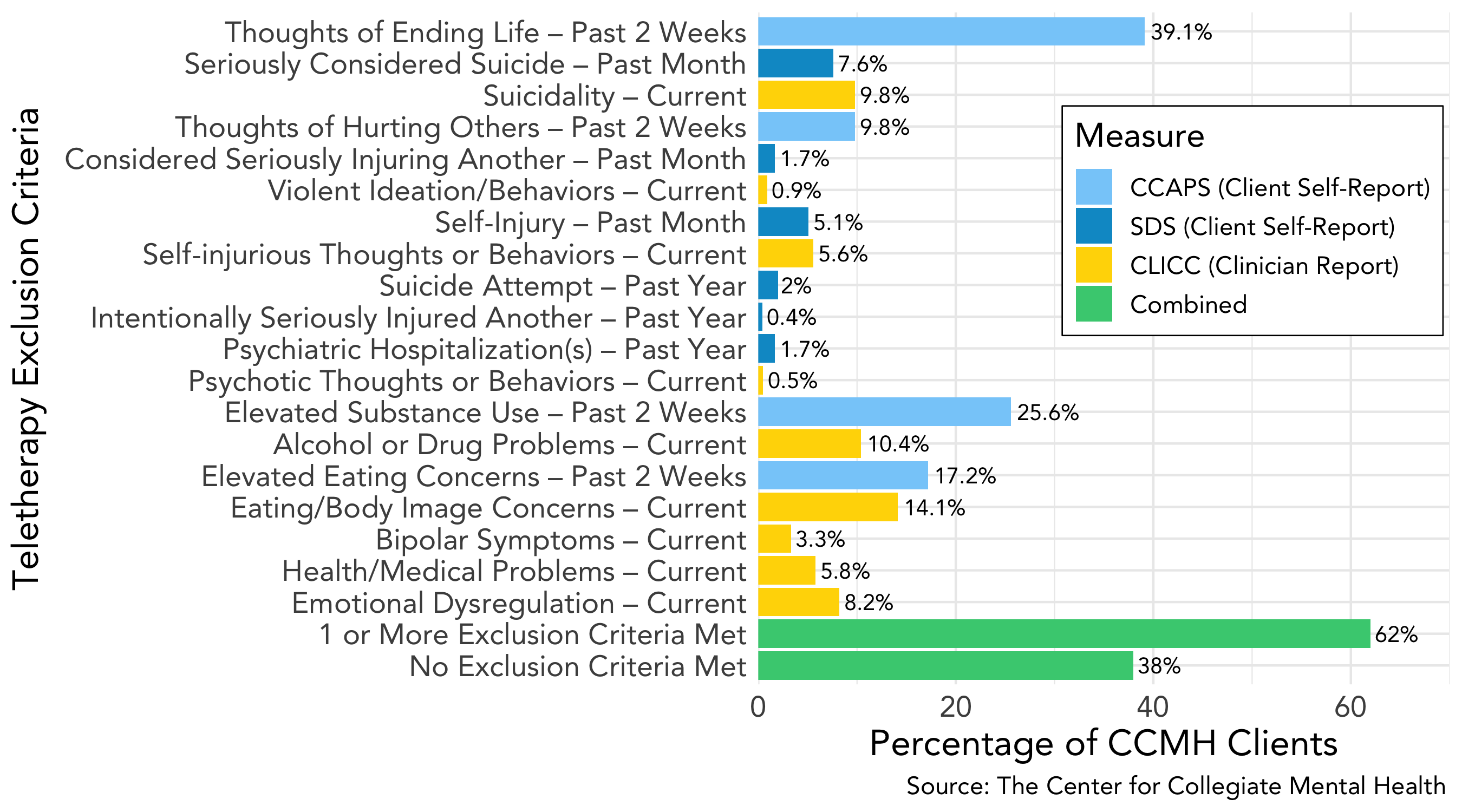

To answer these questions, CCMH examined data from a national sample of 282,553 clients who sought treatment from 172 college counseling centers between 7/1/2018 and 6/30/2020. Each exclusion criteria was paired with the most closely related clinical information gathered from clients and clinicians who completed the Standardized Data Set (SDS), the Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms (CCAPS), and the Clinician Index of Client Concerns (CLICC) at the client’s initial appointment. It should be noted that these sources of data measure similar content from different perspectives. For example, the CCAPS includes a question that asks students whether they have experienced thoughts of ending their life in the last two weeks, whereas the CLICC ask clinicians to indicate whether suicidality is a “primary concern” that needs treatment for a given student. While both might indicate suicidal ideation is present, they are not necessarily endorsed at the same rate because one instrument is the client’s self-report of a symptom that may/may not be related to their reasons for seeking services, whereas the other measure is the clinician’s assessment of a “primary concern” that needs treatment. To be inclusive of both sets of perspectives, data from clients’ self-report as well as the therapists’ evaluation were included in these analyses.

It is important to note that exclusionary criteria were only used in this investigation if CCMH was able to pair a criterion with an existing data-point collected from clients or clinicians. As a result, several additional common exclusionary criteria were not included in this analysis such as: being less than 18 years of age, lack of access to a private space, lack of access to a reliable device or high-speed internet connection, clients who need a formal assessment, and clients who are referred for mandatory or sanctioned services (student conduct or legal needs). Finally, the criteria examined do not count the rate at which students would decline telehealth services due to a preference for in-person services, which has been documented in a number of studies (Dunbar et al., 2018; Toscos et al., 2017; Travers & Benton, 2014).

Proportion of Students Meeting Common Exclusionary Criteria for External Telehealth Referrals

After common exclusion criteria were applied to our sample of 282,553 clients, we found that up to 62% of clients met at least one of the criteria, with thoughts of end my life in the past two weeks (39.1%), elevated substance use symptoms (25.6%), and elevated eating disorder symptoms (17.1%) as the most common rule-out criteria endorsed (see table 1).

Actual prevalence rates of exclusion criteria will vary depending on accuracy of student self-report, vendor rule out policies, and the specific assessment methods utilized by clinicians and vendors.

Table 1: Prevalence of Telehealth Exclusionary Criteria Within College Students Seeking Counseling Services

In addition, clients with at least one exclusionary criteria used approximately 9.8% more services on average (8.9 appointments) than those with no risk factors (8.1 appointments).

Summary and Suggestions

After the unprecedented shift to tele-services within college counseling centers in March 2020, many administrators and clinicians questioned the role of telehealth and whether external telehealth vendors could become a more widely used resource. While the rapid conversion to tele-operations and incorporation of tele-vendor services have allowed colleges and universities to continue providing mental health services remotely and offer new-found flexibility for centers and students, the results of this study suggest that institutions should be cautious when considering external tele-services and pro-actively consider a broad range of implications.

In summary, this study used a large sample of 282,553 students seeking counseling services from 2018 to 2020 and found:

- Up to 62% of typical counseling center clients could be excluded/refused by external telehealth service providers due to the presence of one or more risk factors. This may underestimate actual rates due to the lack of data on some common exclusionary criteria. Actual exclusionary rates will depend on how a vendor evaluates each risk criteria (e.g., client reported, clinician evaluated, medical records, etc.).

- Students with at least 1 telehealth exclusionary criterion utilize 9.8% more counseling center services than those who have no exclusionary criteria.

It is important to note that these findings do not suggest that 38% of students will necessarily be a good fit with external telehealth services. These 38% of students may also experience barriers to telehealth treatment (lack of private space and device, etc.), a strong preference for in-person services, a problem that can only be addressed by a local provider, and the need for treatment dosages that approximate those with risk factors. Moreover, clinicians at counseling centers provide specialized, locally informed, collaborative, and an institution-specific role in students’ care that has proven to be difficult to replicate via external providers.

In general, it should be highlighted that counseling centers will typically still be expected to care for students who are excluded from external tele-health vendor due to risk factors (perhaps up to at least 62% of students seeking services). These clients, in turn, also appear to require more care, including services that were unavailable for the current analyses (consultations, external collaborations), than students without risk factors. Counseling center staff should be recognized for providing these critical services to at-risk students, even though many would have likely been ruled out from external telehealth services.

In a post-COVID-19 world, it will be important for counseling centers to make the most of unexpected silver-linings – such as being flexible in their approach to different modes of care, including phone and telehealth services. In some cases, where counseling center resources are strained due to the large proportion of students with risk factors who need care, the use of telehealth vendors as supplemental/collaborative services for the students with limited risk factors may be a viable option. However, this study also demonstrates that external telehealth vendors have important limitations and should not be expected to meet the comprehensive needs of colleges and universities seeking solutions to the high demand for mental health services, especially for students representing risk. As the field of collegiate mental health continues to evolve, future research should continue to explore these issues.