The Alignment Model: Using the Clinical Load Index (CLI) to Guide Counseling Center Staffing

Alignment (n) - the proper positioning or state of adjustment of parts (as of a mechanical or electronic device) in relation to each other.

Understanding the Problem

A vexing problem for decades, determining the right staffing level for college and university counseling centers has become an increasingly urgent concern for higher education administrators as the rapidly rising demand for mental health services now consistently exceeds the capacity of many, if not most, counseling centers. As a direct result of this demand/supply imbalance, students may struggle to get the help they need, counseling centers struggle to meet an ever-growing demand with limited resources, parents feel frustrated when seeking help for their children, and administrators are faced with a persistent and serious dilemma, without a simple solution.

Before diving in, readers should note that this blog is intentionally focused on questions related to the provision of actual mental health services by highly trained professionals for students in need, rather than much broader questions of overall student wellbeing. While it is true that mental health providers and centers cannot and should not be expected to attend to all wellness needs, it is also true that the specialized task of providing mental health services must be prioritized and examined individually and strategically in order to be aligned with broader wellness goals and resourcing decisions.

Over the last 50 years, the most widely used guidance to determine counseling center staffing levels has rested almost entirely on the idea that there is a staff-to-student ratio that colleges and universities should aspire towards; in other words, that there is an ideal level of staffing for most institutions. While this aspirational ratio has been adjusted over time in response to growing demand the basic concept remains the same and it is currently set at approximately 1 staff member per 1,000 to 1,500 enrolled students (1:1000 to 1:1500), depending on the institution’s context . While the ratio has led to important advocacy and change at many institutions over the last five decades (as well as legislative support in some states) it has also had the side-effect of providing false confidence to key decision makers who may be looking for a simple answer to a very complex and persistent problem.

To quickly illustrate just one reason the ratio might inspire false confidence, imagine two colleges (College A and College B) that both have 1,000 enrolled students and 1 counselor each, or a 1:1,000 staff-to-student ratio. By implementing this ratio, it appears as if both schools have implemented the same well-established guidance and should therefore have similar outcomes. However, the percentage of enrolled students that use an institution’s counseling center in one year (known as “utilization”) varies widely, from less than 1% to more than 50%. If we locate College A and College B at the ends of this range, the counselor at College A would be responsible for 1% of the student body per year (10 students) whereas the counselor at College B would be responsible for 50% of the student body per year (500 students). In other words, the single counselor at College B would be responsible for 50 times more students than the counselor at College A even though both institutions have implemented the exact same guidance. Making matters worse, imagine that the counselor at College B (responsible for 500 students per year) rightfully advocated for more resources and was told by their administrators that they already meet the recommended staffing level and that perhaps they were doing something wrong. The chart below illustrates the magnitude of differential outcomes by implementing the same guidance at two very different institutions:

To add texture to the implications of these divergent outcomes, imagine you are the counselor responsible for the mental health care of either 10 or 500 students per year and ask yourself these questions:

- Will students need to wait to meet with you? Will there be complaints?

- Which level of responsibility would you prefer?

- Which group of students will receive more treatment? The “right” treatment?

- How will you decide which students should receive your services and which ones will not?

- How will the students feel receiving your services?

- Will parents be satisfied?

Setting aside other problems with the ratio, this one example should make clear that reliance on the student-to-staff ratio can result in vastly different mental health service outcomes which can lead to a wide variety of problems among key stakeholders (students, parents, counseling center staff, and administrators). To provide more accurate and useful guidance, CCMH initiated the development of the Clinical Load Index (CLI) in 2018, a metric for accurately measuring/comparing counseling center’s staffing levels across institutions. Importantly, this effort was supported and endorsed by the organizations responsible for the original staff-to-student ratio: the International Accreditation of Counseling Services (IACS) and the Association of University and College Counseling Center Directors (AUCCCD). Because the Alignment Model presented in this blog uses the CLI, a brief primer is provided below. (Readers are also encouraged to learn more about the CLI here.)

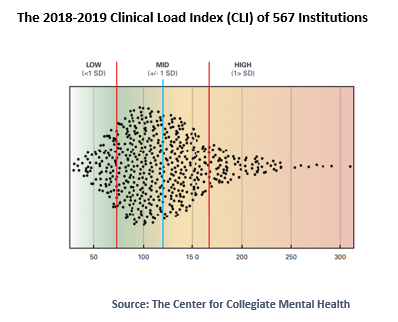

The CLI is created annually by gathering several key data points from more than 650 counseling center members of CCMH. The data from each counseling center is converted into a numerical score representing the standardized “clinical load” of each counseling center/institution. Collectively, these scores represent a distribution of “clinical load” scores, or the Clinical Load Index (CLI). An individual CLI score was intentionally designed to promote a common and intuitive understanding across a diverse range of stakeholders from students to parents to staff to administrators. In 2018-2019, CLI scores ranged from 30 to 310 and each score can be thought of as the average annual caseload of students for a “standardized counselor” or even more simply, the “standardized annual caseload”. Subsequent research on the CLI conducted by CCMH (2019, 2020 reports) has found that CLI scores are associated with a range of related factors including the typical practices implemented by counseling centers and the treatment received by students. In other words, while the CLI score is just a number, that number conveys critical information about typical counseling center practices, reasonable limits to services, and student outcomes. Indeed, CCMH research has found that high CLI scores are associated with less treatment and less symptom improvement.

Alignment Model for Counseling Center Staffing

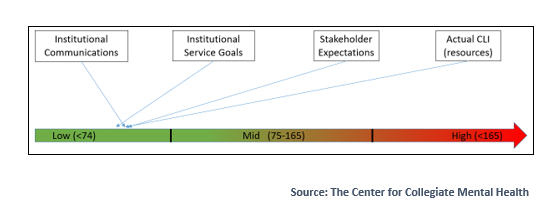

Because the CLI is designed to describe the full range of staffing levels implemented by institutions, CCMH does not recommend a single staffing level or an “ideal CLI score”. Instead, the annually updated range of CLI scores provides a common language that can be used to accurately measure, compare, and discuss a counseling center’s clinical capacity, clinical limits, and clinical opportunities. While a counseling center’s clinical services will look very different at the ends of the CLI spectrum, all CLI levels can theoretically be implemented if staffing, funding, clinical practices/limits, institutional expectations, institutional messaging, and stakeholder expectations (students, parents, community members) are intentionally aligned around the realities of a given CLI. This idea (alignment of expectations and messaging around a common metric) offers the foundation for what CCMH is calling the Alignment Model for counseling center staffing.

Example: Alignment with a High CLI

To further illustrate this framework, let’s begin with an example of an institution that is well aligned with a high CLI. Consider an urban, cash-strapped community college that just hired its very first counselor to serve a population of 15,000 students, most of whom are non-traditional (e.g., older than 18-22) commuter students (they do not live on campus, may be working, and likely live away from the campus). There are a multiple community mental health centers nearby and most students are trying to squeeze classes in between other life demands (children, work, etc.) As a result, utilization is quite low (just 300 students or 2% of the population) and this leads to a CLI of about 300 (click here to learn more about calculating the CLI ). All stakeholders understand that the counselor is only able to provide brief support, crisis intervention, and basic assistance with off-campus referrals (e.g., case management). Students, administrators, and community members all understand (and communicate consistently) that this resource is primarily a triage/referral service. While everyone agrees that more (staff, resources, space, etc.) would be better, they are also thrilled to finally have this new resource in place after many years of advocacy. The counselor feels empowered to make independent decisions about each student served and knows that a decision to refer students out will be supported by their supervisor and the institution. The relatively low utilization rate combined with aligned stakeholder expectations and shared recognition of the achievement represented by the position, means that this less-than-ideal CLI can be successfully implemented and meet critical but limited needs of the institution.

Example: Alignment with a Low CLI

By contrast, consider a small/private well-endowed school, located in an isolated rural setting, that advertises a supportive educational experience with an institutional mission that is focused on a comprehensive approach to student’s interpersonal development. There are no accessible community providers. The counseling center employs 15 clinicians to serve a population of 1,500 students where 40% of the student body (600) will receive individual counseling every year without limits and without nearby referral options (a CLI of about 40). Parents expect that their children will get individual counseling quickly if they need it in this rural location and recognize that they are paying a premium for this educational environment that prioritizes a supportive/developmental experience. Staff who work in the center understand that their role is to focus intensively on supporting overall student development through the provision of long-term insight-oriented counseling for those in need along with routine crisis support. While this is a resource-intensive staffing level to implement, the resource commitment by the institution is consistent with the mission and messaging of the institution which is also explicitly aligned with parent/student expectations and related costs.

These examples illustrate how two extreme staffing levels (and service types) can be successfully implemented if the constituents are aligned with resource levels.

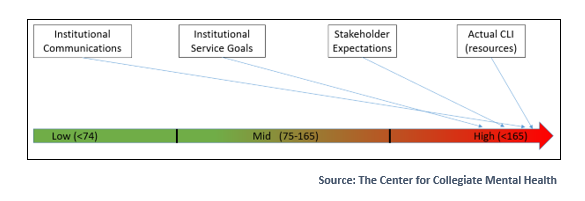

Example: Misalignment with a Changing/High CLI

The following offers one example of a misaligned institution that is surprisingly common. Imagine a mid-sized public institution (15,000 enrolled students), located in a mixed rural/semi-urban location, where enrollment has increased steadily over the last decade, and the counseling center has grown slowly from 8 to 11 staff. During the same period, the number of students seeking services has tripled from 900 to 2700 per year (representing a CLI shift from roughly 112 to 245). A decade ago, the counseling center had only brief waits for service and provided individual counseling with few limits. Staff were attracted to work in the center by the opportunity to provide a range of services that emphasized identity development and longer-term counseling for students in need. Today, the counseling center employs an array of demand management strategies including a phone triage system, stepped-care, mandatory groups for some concerns, off-campus referrals, and long waiting lists with a limit of 3 individual sessions per student per year. Because the school is in a competitive size/price/geographic bracket and the new leadership is looking to grow enrollment to cover growing costs, a marketing campaign was employed that emphasizes intensive individual support from matriculation to graduation. Student services are heavily promoted in advertising, tours, student/parent orientation, and even on the buses. At the same time, the counseling center’s budget was decreased by 10% along with all other student services. As a result, students who seek services (and their parents) are upset with the counseling center and the institution, the administration is upset with the counseling center, students with serious needs go without treatment, and counseling center staff are burned out and leaving to find less stressful jobs that are more consistent with their career goals. The reality of the marketplace and semi-rural location means the center also struggles to recruit new staff. This recruitment/retention dynamic is resulting in multiple unfilled vacancies, poor morale, and further decreased capacity. Upper levels of leadership have publicly criticized the counseling center on several occasions due to the wait for services. Cumulatively, this institution’s approach to staffing its counseling center is poorly aligned at all levels: institutional growth, adjusting expectations over time, budget commitment, messaging to potential stakeholders, messaging to current stakeholders, stakeholder expectations of the center, and staff-member’s experience of being caught in the middle.

Determining Your Staffing Level using the Alignment Model

Because staffing levels, resources, scopes of services, institutional missions and goals vary widely, the Alignment Model does not recommend a specific staffing level. Instead, this approach recommends a careful evaluation of resources including the CLI of the counseling center, institutional mission and priorities, and the expectations of all stakeholders to reach alignment. Achieving alignment may require numerous changes over many years or relatively minor adjustments within one year, but even a single point of stakeholder misalignment will cause significant stress for all stakeholders.

Signs of Misalignment:

When an institution is coping with misalignment in their approach to mental health services, it will be common to see counseling center leadership receiving criticism from stakeholders who want more access, faster access, or greater amounts of specific services (e.g., individual counseling). Students and others may be active in social media/media outlets publicizing specific experiences or complaints, administrators may feel that they are constantly being critiqued for a lack of services, counseling center staff may complain that they are simply unable to provide what is promised to students and feel concern about providing ethical care that is consistent with their training and mandate; and students/parents may report that the services they were told to expect are simply not available. While dynamics like these may be present on all campuses to some extent, we recommend attending to the pattern and intensity of across stakeholder groups when evaluating whether misalignment exists and how to fix it.

Signs of Alignment:

When an institution is aligned in their approach to mental health services, many of the challenges listed above will not occur or will occur relatively infrequently and with lower intensity. An individual sign of misalignment may also be due to misinformation that simply needs to be corrected. Institutional leadership are likely to communicate messages about mental health services that are supportive, and which intentionally integrate information about known service limits and the rationale. For example, an effective leader at a large public/urban institution might say, “While we are a large institution with limited resources, we are surrounded by resource options in our community and proud that our counseling center is consistently able to provide rapid access to crisis services and short-term treatment along with outside referrals for long-term care.” A conversation with almost any stakeholder (student, parent, faculty, staff, reporter, student government, etc.) will generally reveal broadly similar understandings of available services and the rationale for why that level of service exists. Ongoing dialogue/debate about the level of service will exist – but all stakeholders will share a common understanding of what is available, and why.

Pursuing Alignment at your Institution

- Step 1: Understand your CLI score: Take time to carefully calculate the CLI of your counseling center and try to determine if it has changed in recent years. Use CCMH resources as a guide. Your CLI score will provide the foundation for each of the next steps and is worth taking time to get right. If your center does not have an annual practice for determining each clinician’s clinical contribution per week (in expected hours) this will be important in tracking your CLI over time in addition to achieving a balance between system/clinician needs.

- Step 2: Self Evaluation: Set aside sufficient time and space for an appropriately representative group of college and university leaders to carefully explore the following questions:

- What is our institutional mission? What are our institutional priorities related to mental health? Are these accurately reflected in current resourcing and service offerings/experiences?

- What experience do we want our students to have when they seek mental health services? For example: rapid access to triage with routine external referrals for long-term care or quick access to long-term individual counseling with few limits?

- When students seek mental health services, what limits are acceptable to the institution? Which limits are not acceptable? Is it OK to have a treatment limit? (per year or career?) Is it OK to have a wait for individual counseling and what length of wait is acceptable? Are all students eligible or just some?

- What do we currently tell our students and stakeholders to expect regarding mental health services? Where do we explain our scope of services and with how much detail (e.g., tours, marketing, admissions, orientation, faculty/staff training, etc.). A “scope of service” statement explains in common sense language the overall approach of the center along with any limitations on access or scope of treatment provided.

- Are we in a position to increase our commitment of resources (staffing, office-space, etc.) to mental health services? If not, why, and is this widely communicated?

- What resource limits must be in place for fiscal, operational, or mission-related reasons?

- Counseling center review – as discussed above, college and university counseling centers can take many different forms and provide many different types of services and the details of clinical system implementation do matter. Taking time to fully understand what your counseling center provides and how they operate will help to understand the unique nuance of your counseling center and whether change or adjustments are possible and/or worth exploring. An external review by a member of IACS, AUCCCD, or CCMH can assist in offering an objective perspective.

- Step 3: Stakeholder review: A group of university leaders should then seek to explore the same questions above with as many stakeholder groups as possible including:

- Current/prospective students and alumni

- Current/prospective parents of students

- Faculty and staff who routinely interact with students

- Institutional leadership (boards, regents, presidents, provosts, VP’s, etc.)

- Community members (anyone who might interact with students and mental health) including community providers.

- Counseling center staff and others who provide mental health services on campus.

- Step 4: Goal Setting for Alignment: With the quantitative and qualitative data gathered above, the next step is to define which changes will be necessary to achieve alignment. Achieving alignment could require minor tweaks to institutional messaging or service descriptions (e.g., a scope of service statement) or it could be a complex multi-year endeavor involving capital spending for new office-space, fund-raising, a review of counseling center operations, and top-to-bottom rethinking of institutional priorities and communications. Regardless of the exact changes needed, the resulting alignment of mental health resources with all stakeholder expectations and related communications/messaging will provide the foundation for a successful implementation of the CLI selected by the institution. Here are some examples of changes that institutions might need to make to achieve alignment:

- Adjust institutional messaging (PR, tours, new student orientation, referral channels, etc.) to convey accurate expectations for the level of mental health services (and limits) to all stakeholders in a consistent manner. Evaluate, adjust, and repeat annually.

- Increase resources for the counseling center to reach the target CLI identified through the steps described above.

- Adjust the services offered by a counseling center to be consistent with the existing CLI and communicate these changes effectively and consistently to all stakeholders.

- Develop a broad range of potential mental health and wellness resources for the students to decrease the rate of referrals to the counseling center.

Conclusion

The landscape of higher education has changed dramatically in the last 50 years as has the demand for, and complexity of providing, mental health services to a diverse set of students across a diverse set of institutions. While there is no simple/universal solution for all institutions, the combination of an accurate/comparable metric for comparing counseling center capacities (the CLI) and the conceptual framework outlined in this “Alignment Model” blog, provide an easily accessible starting point and scaffolding to begin the process of pursuing alignment between stakeholders’ expectations of mental health services and an institution’s actual resources to deliver those services, including the institution’s choice and funding of a given CLI. If your institution would like more information about the CLI or the Alignment Model, please contact CCMH.