Presenting Concerns in Counseling Centers: The View from Clinicians on the Ground.

This blog is a summary of a CCMH study on presenting concerns in counseling centers published in 2017.

Pérez-Rojas, A. E., Lockard, A. J., Bartholomew, T. T., Janis, R. A., Carney, D. M., Xiao, H., Youn, S. J., Scofield, B. E., Locke, B. D., Castonguay, L. G., & Hayes, J. A. (2017). Presenting concerns in counseling centers: The view from clinicians on the ground. Psychological Services, 14(4), 416–427. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000122

A growing body of research over the last several years has highlighted significant increases in both the demand from college students for mental health treatment services and the severity of clinical concerns among treatment-seeking college students at university counseling centers (UCCs) 1,2,3. While such efforts shed important light on who is seeking treatment and how UCC services are utilized, a knowledge gap persisted in the literature pertaining to why students are pursuing counseling. In a previous study using CCMH data, Pérez-Rojas et al. (2017) aimed to address this void by examining the presenting concerns of students seeking services at UCCs nationally. Specifically, to complement prior smaller studies (e.g., single-site studies) or ones drawing from surveys of counseling center directors or self-reports of client distress, the study focused on UCC clinicians’ evaluations of their clients’ presenting concerns.

The authors’ decision to examine presenting concerns from the perspective of UCC clinicians was informed by several considerations:

- Clinicians have direct and frequent contact with clients.

- Clinicians frequently have access to multiple sources of client data (e.g., student records, family histories, self-reports of distress, etc.).

- Surveys of counseling center directors typically are not intended to provide precise clinical data.

- Clients’ self-reported distress may speak more to their overall functioning and may not adequately reflect why they are seeking treatment or what they hope to address in counseling.

Using a CCMH dataset consisting of 53,194 clients seen by 1,383 clinicians across 84 UCCs, Pérez-Rojas et al. (2017) conducted descriptive and exploratory analyses to address three research questions:

- What concerns do clinicians most frequently identify in the overall client populations as well as from specific sub-populations at intake?

- To what extent do clinicians’ ratings of client presenting concerns differ by client identity characteristics?

- What is the comparative ranking and prevalence of suicidality as a presenting concern for UCC clients overall as well as for specific subgroups?

The researchers reviewed clinicians’ ratings of clients’ presenting concerns as indicated on the Clinician Index of Client Concerns (CLICC). The CLICC is a checklist of common presenting concerns that clinicians complete after a client’s initial session. Clinicians are asked to assess the client’s primary concerns from the checklist and then indicate the topmost concern from those selected. The study focused on all primary concerns assessed by clinicians to best understand the prevalence of client concerns. Additionally, they further concentrated on the top five concerns to make findings more readily applicable to clinical work. Demographic data were collected via the Standardized Data Set (SDS)

Study Findings

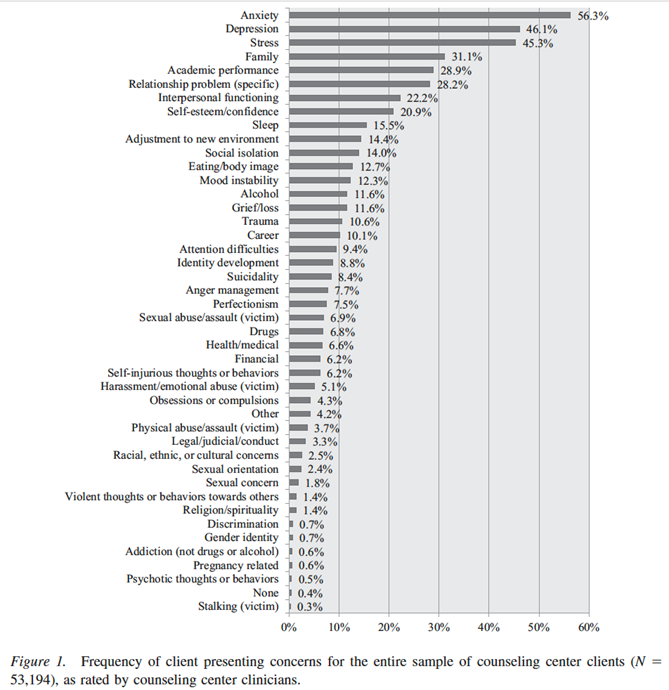

The following figure is reproduced directly from the article and demonstrates that, across all clients in the study sample, the five most common presenting concerns indicated by UCC clinicians were (a) anxiety, (b) depression, (c) stress, (d) family, and (e) academic performance. Overall, suicidality was the 20th most-frequently indicated presenting concern (selected by clinicians for 8.4% of clients).

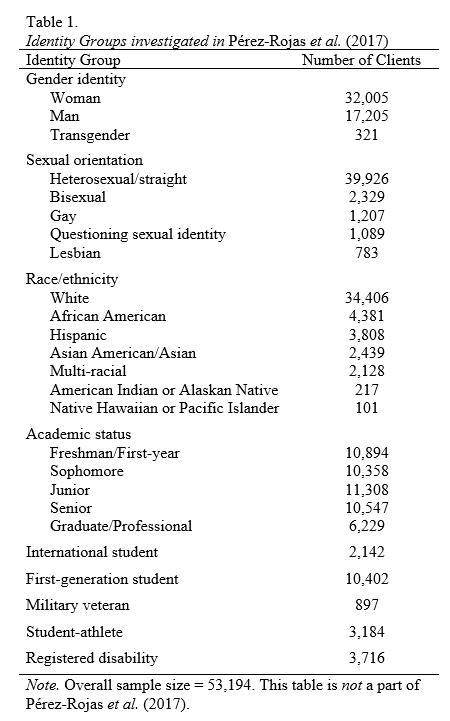

To compare presenting concerns across different client populations, the researchers investigated several identity variables (see Table 1 below).

Pérez-Rojas et al. (2017) rank-ordered the top five clinical concerns from most-frequently to least-frequently endorsed and compared these rank orders across these 25 identity groups.

Key takeaways from these comparisons include:

Anxiety, depression, and stress:

- With the exception of one group (clients identifying as Transgender), all identity groups shared the same top three CLICC clinical concerns in varying rank orders: anxiety, depression, and stress.

Family and academic performance:

- For most client groups (16 out of 25, 64%), clinicians assessed family as the 4th most frequent clinical concern, and academic performance as the 5th most prominent clinical concern (11 out of 25, 44%).

Additional common presenting clinical concerns:

- Relationship problems and adjustment were the next most-frequently identified concerns across client identity groups. Adjustment concerns were most commonly identified among international students and Freshman/first-year students.

- For students who identify as Questioning in terms of their sexual orientation, interpersonal functioning was also a frequently assessed presenting concern.

Transgender clients:

- The rank-order of presenting concerns assessed by clinicians differed the most from the overall sample for clients who identified as Transgender (n = 321). The most frequent presenting concern among transgender clients was gender identity (which ranked 39th across the overall sample).

- Clients who identify as Transgender also were the only clients for whom identity development ranked in the top 5 concerns (ranked 5th for transgender clients vs. 19th across the overall sample).

- Anxiety, depression, and stress (CLICC rank-orders two through four, respectively) remained prevalent among this group as well.

As noted earlier, the study found that suicidality was the 20th most frequent presenting concern endorsed by clinicians. Across the 25 identity groups, rankings ranged from 12th (transgender students) to 26th (Graduate/Professional students). The identity groups where suicidality was most prevalent included students identifying as transgender and questioning their sexual identity (17.9% and 17.3%, respectively, versus 8.4% across all clients in the study). Several other groups demonstrated moderately higher clinician endorsement rates than the overall student sample: bisexual clients (14.6%), American Indian or Alaska Native clients (12.0%), lesbian clients (11.6%), Asian American/Asian clients (11.2%), Freshman/first-year clients (11.1%), multi-racial clients (11.0%), gay clients (10.9%), and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander clients (10.9%).

Implications of Findings

The following takeaways were noted:

- These findings confirm that UCC clinicians and staff should provide adequate resources (e.g., training, professional development, and service allocation) to assess and manage common client concerns related to anxiety, depression, stress, family, and academic performance. Given the prevalence these concerns across various identity groups, additional treatment modalities such as group therapy and outreach programs may be important to consider.

- While findings show far more similarities than differences across identity groups, important differences emerged with specific identities, particularly clients who identify as Transgender. The authors suggested that many transgender clients may primarily seek treatment to aid in identity development processes (e.g., personal growth, help with gender transitions), which may co-occur with (or exacerbate) other concerns such as anxiety, depression, and stress.

- Suicidality was a disproportionately a more common presenting concern in clients with a underrepresented identity. The researchers argued such findings aligned with the concept of minority stress (i.e., that members of cultural minority groups experience frequent, harmful stressors related to prejudice, oppression, and discrimination, which can negatively impact mental health). Outreach, early identification, and prevention programs may be particularly helpful to implement with these groups of students. Additionally, these findings highlight the importance of continued/enhanced staff development and trainings pertaining to gender- and racially/ethnically-diverse clients.

*For additional information on presenting concerns of various demographic groups, please also visit this recent CCMH blog post!

This blog post was written by CCMH Business Team member, Ryan Kilcullen, M.S. Ryan is a Doctoral Student in Clinical Psychology at PSU and a part of the Castonguay Lab.