Native American Students in College Counseling: Are Symptoms Related to Racial/Ethnic Diversity on Campus?

Native American Students in College Counseling: Are Symptoms Related to Racial/Ethnic Diversity on Campus?

Highlights:

- Many Native American students report elevated psychological and academic distress symptoms when they present to university counseling centers.

- Native American clients at more racially/ethnically diverse campuses report slightly lower academic distress than those at less diverse institutions.

- Increasing representation of diverse students at colleges and universities may be one part of a multi-faceted approach to help create a sense of belonging and academic self-efficacy among Native Americans. Supports to address disparities in psychological and academic distress among Native American students are also needed.

Native American and Alaska Native individuals (hereafter referred to as Native Americans) have made profound contributions to higher education, including in the fields of medicine, public policy, education, and the arts (Academic Influence, 2023; American Neurological Association, n.d.). Because Native American students have traditionally been marginalized in the U.S. educational system (Fish & Syed, 2018), there have been efforts to increase access to college for the Native community (e.g., American Indian College Fund). However, Native Americans are still substantially under-represented at U.S. colleges and universities (Brayboy et al., 2015; Postsecondary National Policy Institute, 2023) and often report social isolation, disconnection from cultural traditions, and racial discrimination in college (Brayboy et al., 2015; Tachine et al., 2017).

Research suggests that greater representation of diverse racial/ethnic groups at colleges and universities may help Native American students develop a stronger sense of well-being and commitment to their university (Benally et al., 2020; Rodriguez & Mallinckrodt, 2021; Strayhorn et al., 2016; Tachine et al., 2017). However, it is unclear whether the racial/ethnic makeup of colleges and universities is associated with mental health symptoms among Native American students who seek services at university counseling centers (UCCs). While university counseling UCCs have been shown to effectively support Native American students struggling with mental health concerns (Isadore et al., 2024), a better understanding of how the diversity of academic institutions relates to Native American students’ symptoms could inform efforts to identify resources to increase belonging and well-being for these students.

In this blog, we examined psychological and academic distress among Native American students and tested whether racial/ethnic diversity on college campuses in general, and the representation of Native American students in particular, were associated with Native American students’ symptoms when beginning treatment at UCCs. Specifically, we examined the following questions regarding Native American students in college counseling:

- How do Native American clients’ psychological and academic distress symptoms compare to those of other racial/ethnic backgrounds?

- Do Native American clients who attend more racially diverse college campuses report different levels of academic and psychological distress symptoms than those at less diverse campuses?

To answer these questions, we used data from 303,407 clients (1,651 of whom identified as Native American) who received counseling at 146 UCCs from 2021 to 2023. Clients’ symptoms were measured using the Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms-62 (CCAPS-62) at the beginning of treatment. Specifically, we used the CCAPS-62 Distress Index (a measure of psychological distress, such as depression and anxiety symptoms) and the Academic Distress subscale, which measures students’ academic difficulties and confidence that they can succeed in school. Data on the racial/ethnic makeup of students’ college or university was taken from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System for the 2022-2023 academic year.

How do Native American clients’ psychological and academic distress symptoms compare to those of other racial/ethnic backgrounds?

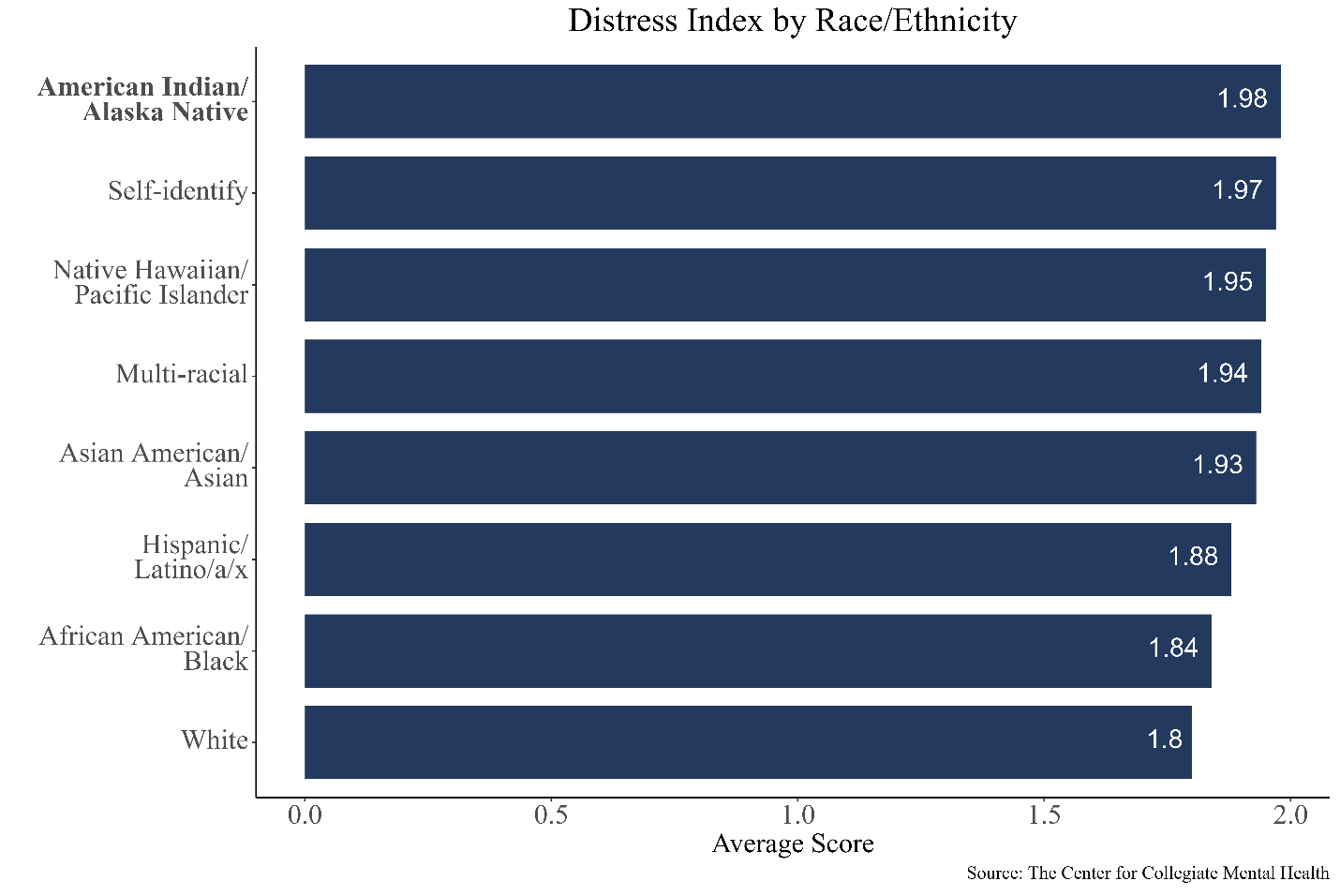

Overall, psychological distress levels were similar across racial/ethnic identities at the beginning of counseling, with Native American clients reporting the highest levels of symptoms. This was followed by clients who self-identified their race and those who identified as Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. Clients who identified as White reported the lowest levels of psychological distress.

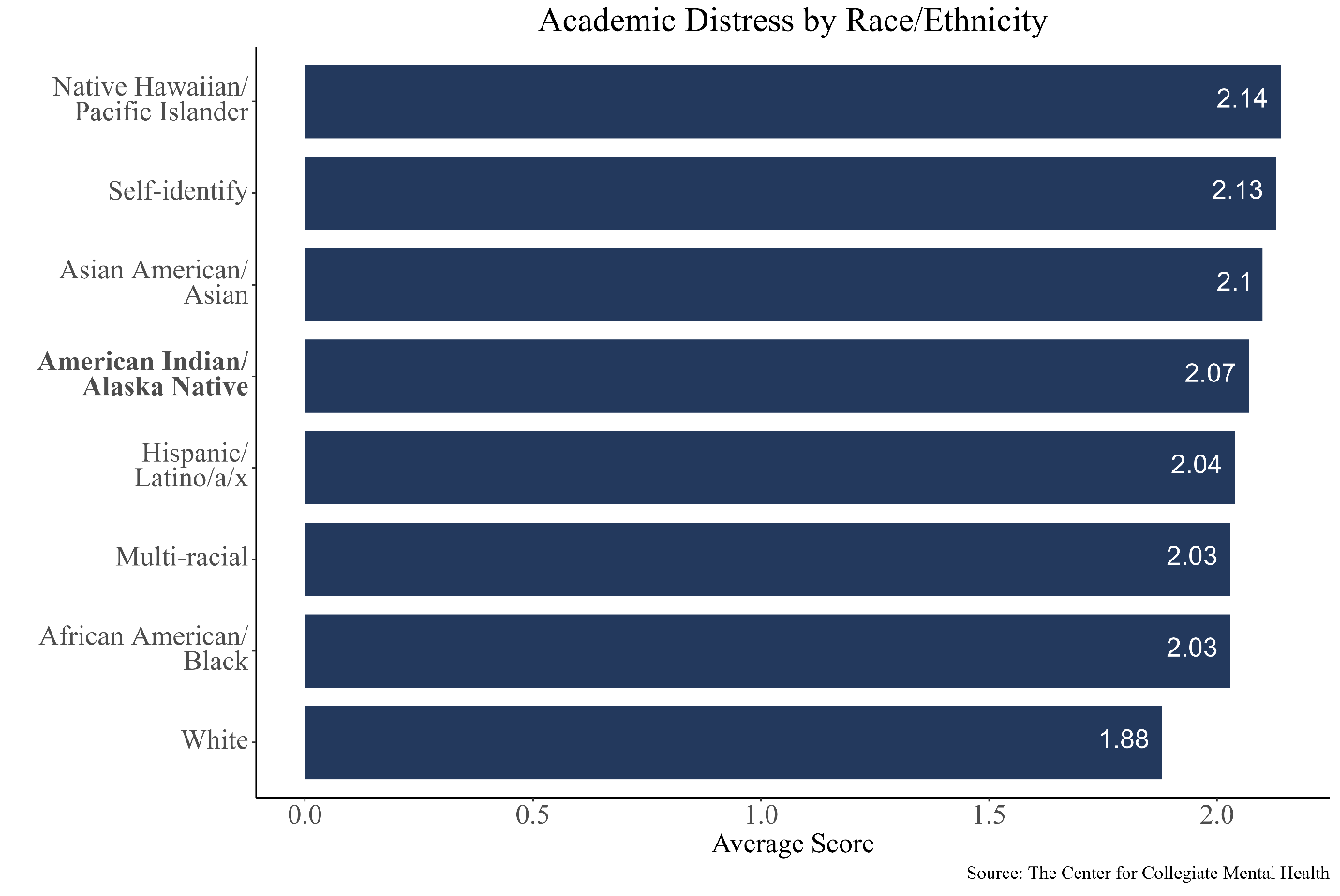

Native American clients’ academic distress at the beginning of counseling was similar to the levels reported by other students of color. Racial/ethnic groups reporting the highest academic distress were Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, self-identified, and Asian American/Asian clients. Clients who identified as White reported the lowest levels of academic distress.

Do Native American clients who attend more racially diverse college campuses report different levels of academic and psychological distress symptoms than those at less diverse campuses?

Native American clients at institutions with a higher proportion of students from minoritized racial/ethnic identities reported slightly lower academic distress at the beginning of counseling than those at less racially/ethnically diverse schools (see Appendix for results of statistical tests). Additionally, Native American clients at institutions with a higher proportion of Native American students specifically reported marginally lower academic distress. This indicates that on average, Native Americans at more racially/ethnically diverse institutions (and those with more Native American students) report slightly lower academic distress when beginning treatment at UCCs, though these differences are small.

Native American students’ psychological distress at the beginning of counseling was unrelated to the percentage of students at their college/university who identified as racially diverse. Furthermore, their psychological distress was equal regardless of the percentage of Native Americans in the general student body. This means that Native American students report similar levels of psychological distress at the beginning of counseling regardless of the level of racial/ethnic diversity on campus.

Summary

On average, students who identify as Native American present to UCCs with higher symptoms of psychological distress (i.e. depression, generalized anxiety, social anxiety, academic distress, and frustration/anger symptoms) than those of other racial/ethnic identities.

Native American students begin counseling with similar levels of academic distress as other racially/ethnically minoritized students (e.g., concerns about academic performance, confidence in their ability to be successful in school). Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander clients reported the highest levels of academic distress, while White students reported the lowest levels.

Native American clients attending more racially/ethnically diverse college/universities—including institutions with a higher proportion of Native American students—reported slightly lower academic distress than Native American clients at less diverse schools. However, racial/ethnic diversity at colleges and universities was unrelated to Native American clients’ general psychological distress when they began counseling. This suggests that the racial/ethnic diversity at an institution is modestly related to Native American clients’ perceptions of their academic abilities and likelihood of succeeding in college rather than their mental health symptoms. In the future, it may be useful to clarify why this is the case (e.g., whether the representation of Native American students itself influences academic distress or whether institutions that are more supportive of Native American student success attract more Native students).

Implications

UCC clinicians and leadership should be aware that Native American clients may be at higher risk for elevated mental health symptoms than students from other racial/ethnic backgrounds, which is likely due to systemic factors (Fish & Syed, 2018). As such, services for these students should be responsive to the potential causes of elevated symptoms in this population (e.g., discrimination, lack of access to resources and supports, community and intergenerational trauma). UCC staff may facilitate Native American students’ sense of belonging at the university by helping them build social connections with a diverse range of individuals on campus (Strayhorn et al., 2016).

While prior research has shown that UCCs are equally effective at treating Native American clients, they may still end treatment with higher distress than clients from other racial/ethnic backgrounds (Isadore et al., 2024). UCCs may need to be mindful of whether additional services outside of the counseling center are indicated for Native American students with more chronic or severe concerns, such as referral to longer-term counseling or psychiatric services outside of the university.

Although the relationship between racial/ethnic diversity on campus and academic distress was modest, it is consistent with reports of marginalization by Native American students in higher education (Brayboy et al., 2015; Tachine et al., 2017). The small magnitude of the relationship suggests that beyond the racial demography of the student body, access to comprehensive, proactive, and adjunctive services is crucial to support Native American students. This may include working to recruit more Native American students, being responsive to their academic needs, and providing access to campus mental health services. Academic institutions may also help support this population by adopting evidence-based programs that increase connection with and commitment to the university, such as multicultural spaces on campus that focus on bringing Native American students together (Tachine et al., 2017).

References

Academic Influence. (2023, July 28). Influential American Indian Scholars. Https://Academicinfluence.Com/Rankings/People/Influential-American-Indian-Scholars.

American Neurological Association. (n.d.). Native American Pioneers in Medicine. Https://Myana.Org/Native-American-Pioneers-Medicine.

Benally, S., Pepion, K., & Rochat, A. (2020). Bridging the Gap in Native American Attainment in Higher Education: The Role of Native American-Serving Nontribal Institutions. www.equityinhighered.org

Brayboy, B. Mk. J., Solyom, J. A., & Castagno, A. E. (2015). Indigenous Peoples in Higher Education. Journal of American Indian Education, 54(1), 154–186. https://doi.org/10.5749/jamerindieduc.54.1.0154

Fish, J., & Syed, M. (2018). Native Americans in Higher Education: An Ecological Systems Perspective. Journal of College Student Development, 59(4), 387–403. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2018.0038

Isadore, K. M., Hayes, J. A., Cutter, C. J., & Beitel, M. (2024). Native American College Students in Counseling: Results From a Large-Scale, Multisite Effectiveness Study. Psychotherapy. 61, 173-183. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000526

Postsecondary National Policy Institute. (2023, November). Native American Students in Higher Education. Https://Pnpi.Org/Wp-Content/Uploads/2023/11/NativeAmericanFactSheet-Nov-2023.Pdf.

Rodriguez, A. A., & Mallinckrodt, B. (2021). Native American-Identified Students’ Transition to College: A Theoretical Model of Coping Challenges and Resources. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory and Practice, 23(1), 96–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025118799747

Strayhorn, T. L., Bie, F., & Williams, M. S. (2016). Measuring the Influence of Native American College Students’ Interactions with Diverse Others on Sense of Belonging. Journal of American Indian Education, 55(1), 49–73. https://doi.org/10.1353/jaie.2016.a798950

Tachine, A. R., Cabrera, N. L., & Yellow Bird, E. (2017). Home Away From Home: Native American Students’ Sense of Belonging During Their First Year in College. Journal of Higher Education, 88(5), 785–807. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2016.1257322

Appendix

Correlations between the racial/ethnic makeup of the general student body and Native American clients’ symptoms when beginning college counseling.

|

|

Percent Racially Diverse |

Percent Native American |

|

Psychological Distress |

-.02 |

.01 |

|

Academic Distress |

-.09** |

-.07* |

Note. Numbers are Pearson’s r. The term, “racially diverse,” refers to students of races/ethnicities besides White.

*p < .05, and **p < .01.

Published November 18, 2024