Students with Elevated Suicide Risk: The Benefits Provided by Counseling Center Services

Between 2000 and 2022, suicide rates in the United States increased by 36% (Center for Disease Control, 2024). While suicide affects every age and demographic group, it is the second leading cause of death for individuals between the ages of 10 and 34, which encompasses the ages of most college students. Indeed, it is estimated that approximately 1,100 college students die by suicide annually (The JED Foundation, 2002).

Given the gravity of this problem, there have been concerted efforts to enhance suicide prevention programming within higher education over the past two decades. Prevention programs have ranged in size and scope with many interventions implemented that identify at-risk students and refer them to essential support services. Overall, these initiatives appear to have been successful, leading to more students seeking necessary mental health services, particularly those experiencing risk factors for suicide (e.g., past serious consideration of suicide and self-injurious behavior) (CCMH 2015 Annual Report, Healthy Minds Network, 2024). In fact, college students are less likely to die by suicide than their same-age peers in the general population, which may be due in part to the collective services and comprehensive support systems available on college campuses (The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine, 2021).

College counseling centers play a central role in suicide prevention efforts, historically treating a significant proportion of students with elevated suicide risk, including those with prior suicidal attempts and self-injurious behavior. This vital function of centers has expanded over the years, as the percentage of students served nationally at counseling centers with suicidal/self-injurious behavior histories has grown from 26% in 2010-2011 to 30% in 2023-2024. The notable portion of students at counseling centers who report a history of past suicidal attempts or self-injurious behavior is important because these are two of the primary risk factors that increase the likelihood of dying by suicide (Hayes et al., 2020, Van Orden et al., 2010).

While counseling centers have historically treated a considerable segment of students with heightened suicide risk, ongoing questions remain about the complexity of co-occurring problems experienced, the scope of services they utilize, and whether gaps in care exist. In the 2024 Annual Report, CCMH investigated how these students’ clinical characteristics, stressors and contextual factors, service utilization, and treatment outcomes differed from those without these historical risk factors.

In the current investigation the following questions were answered:

- At the beginning of treatment, do clients with histories of suicidal/self-injurious behavior (S/SIB):

- experience higher levels of distress?

- report more severe problems?

- display a greater level of clinical complexity?

- During treatment, do clients with S/SIB histories:

- utilize more services?

- demonstrate a higher rate of critical events?

- At the end of treatment, do clients with histories of S/SIB show improvement in general distress and suicidal ideation that is comparable to students without these risk factors?

Data for the current Annual Report include 302,579 students who were treated at 190 different college counseling centers in the United States from 2021 to 2024. Information was collected from the Standardized Data Set (SDS) – Client Information Form, Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms (CCAPS), and two measures completed by clinicians (Clinician Index of Client Concerns [CLICC], Case Closure Form). The SDS, CCAPS and CLICC are typically completed when students initiate services, and the CCAPS is commonly delivered to students throughout treatment to monitor progress. The Case Closure Form is completed at the end of services.

BEGINNING OF TREATMENT

Levels of Distress

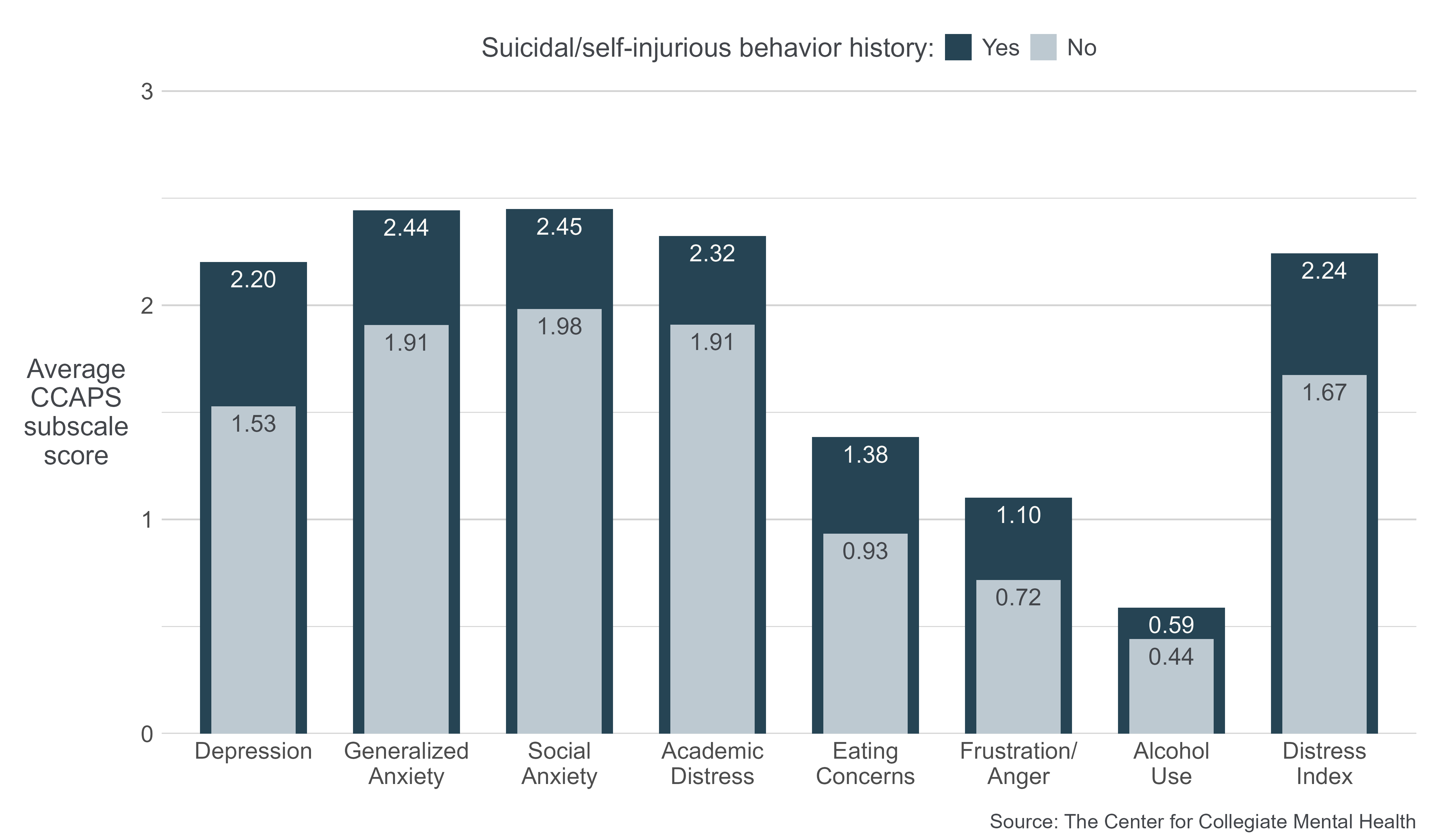

Students with histories of S/SIB enter counseling services with higher levels of self-reported distress on all CCAPS subscales compared to those without a history of S/SIB. The largest differences were discovered in Depression, Generalized Anxiety, and General Distress symptoms. Smaller differences were observed in Social Anxiety, Academic Distress, Eating Concerns, Frustration/Anger, and Alcohol Use.

Presenting Concerns

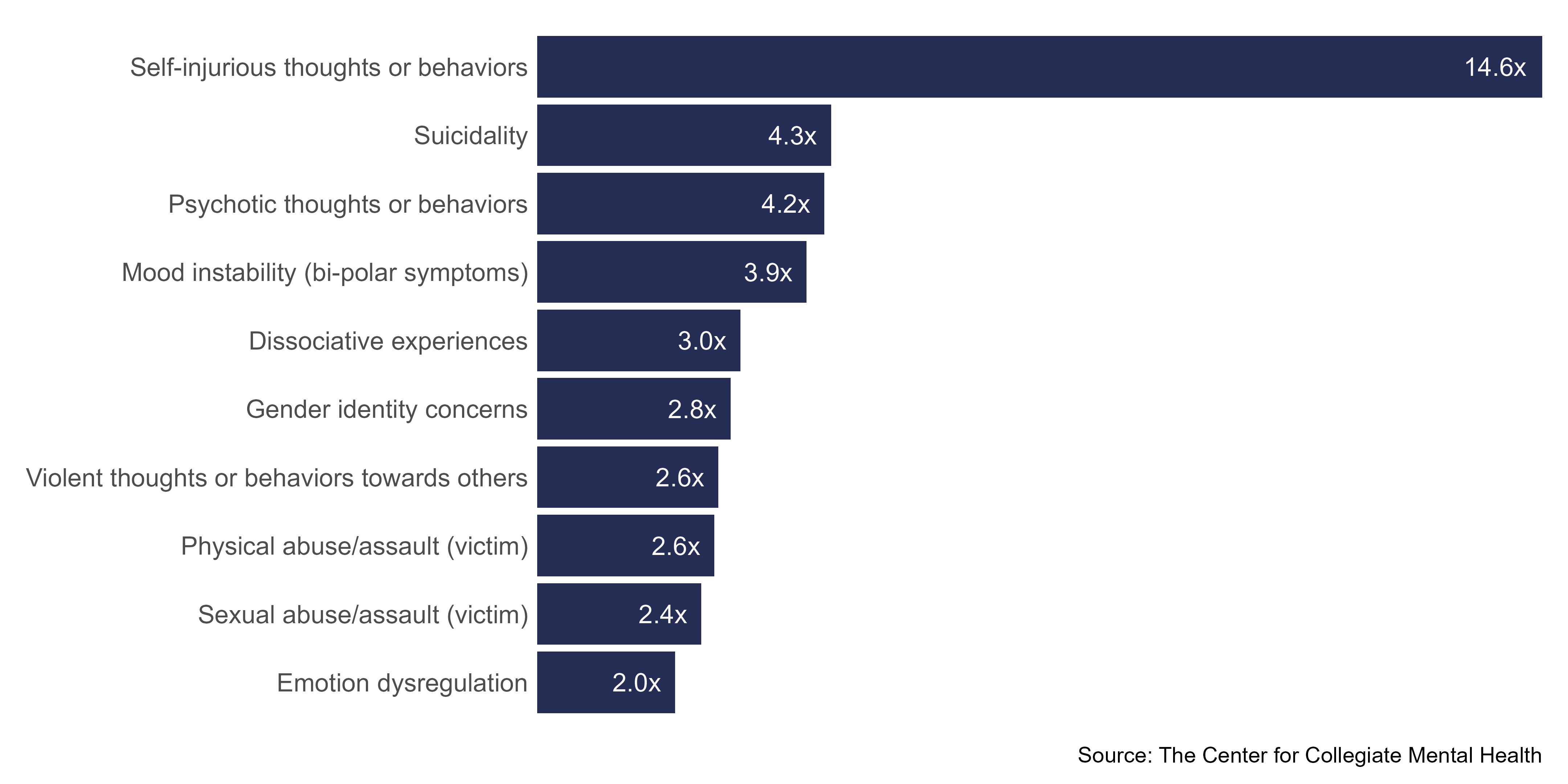

The presenting concerns identified by clinicians for students with and without S/SIB histories differed in several ways. The figure below shows how many times more likely clients with a S/SIB history were to be assessed with a particular presenting concern than clients without past S/SIB. The specific concerns displayed below were chosen for examination because they often indicate that a student is experiencing a high level of distress, impairment, or safety risk.

Students with a S/SIB history were much more likely (14.6 times) to have self-injurious thoughts and behaviors identified as an existing concern at the beginning of treatment. Additionally, they were 3 to 4.3 times more likely to experience dissociation, mood instability, psychotic thoughts or behaviors, and suicidality. Smaller, yet notable differences, were observed in several other presenting concerns, including experiencing abuse/assault, violent thoughts or behaviors, and gender identity concerns.

It is important to note that these concerns were infrequently identified in both students with and without S/SIB histories but at much different prevalence rates. For example, 3.3% of students with past S/SIB and 1.1% of those without these histories began counseling with dissociative experiences as a presenting problem. In other words, regardless of their history of S/SIB, a student has a low likelihood of entering counseling with any of these concerns. However, these results demonstrate that students with S/SIB histories are disproportionately more likely to present to counseling with severe

comorbid problems.

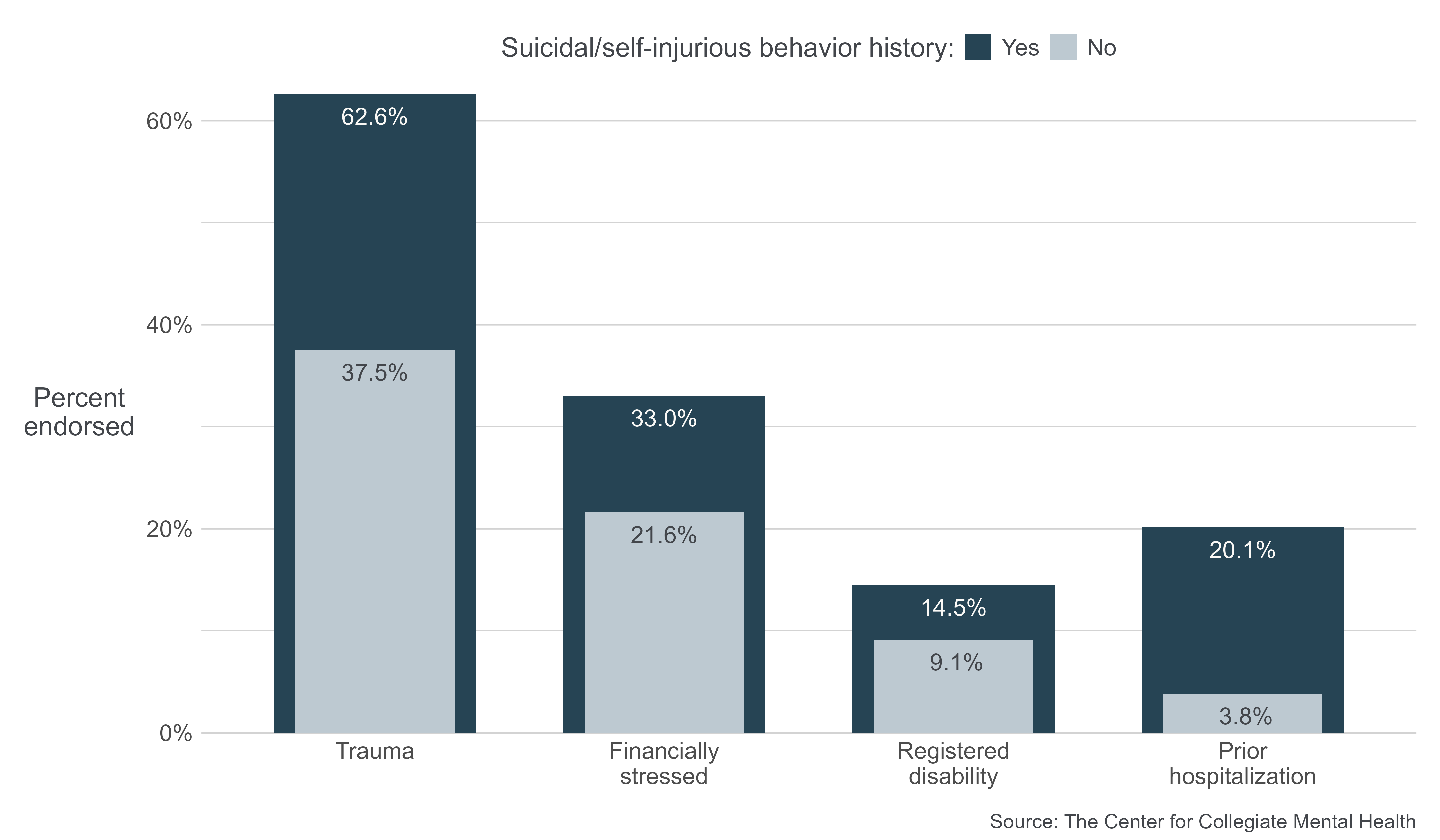

Case Complexity

Students with a history of S/SIB, compared to those without, were substantially more likely to enter services with complex histories and co-occurring stressors. These include a history of trauma and psychiatric hospitalization, as well a current financial stress and disability status. The specific historical and contextual factors shown below were selected for investigation because they often require multi-department or external collaborations (e.g., referrals and/or consultations with Title IX supports, Dean of Students, Financial Aid offices, Disability Services, and external outpatient/inpatient

treatment providers).

DURING TREATMENT

Utilization

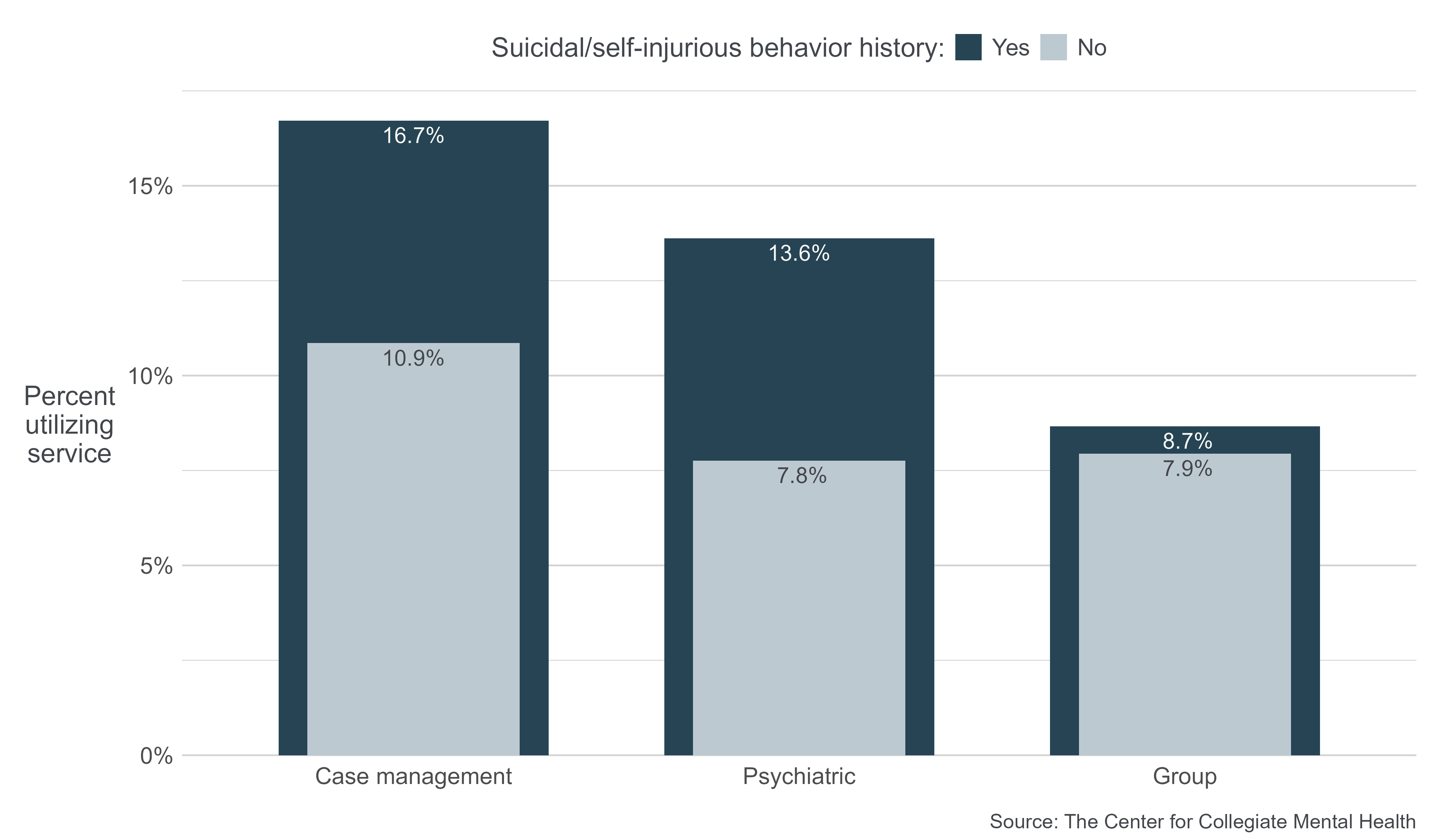

Overall, students with past S/SIB had 1 more total appointments scheduled, on average, than students without these histories, which is equivalent to utilizing 15% more services. Students with and without S/SIB histories were compared in terms of the proportion of each group who utilized various types of comprehensive services offered by some counseling centers. A greater percentage of students with S/SIB histories received case management (16.7% vs. 10.9%) and psychiatric services (13.6% vs. 7.8%), while group therapy was utilized at a similar rate in both groups.

Critical Events

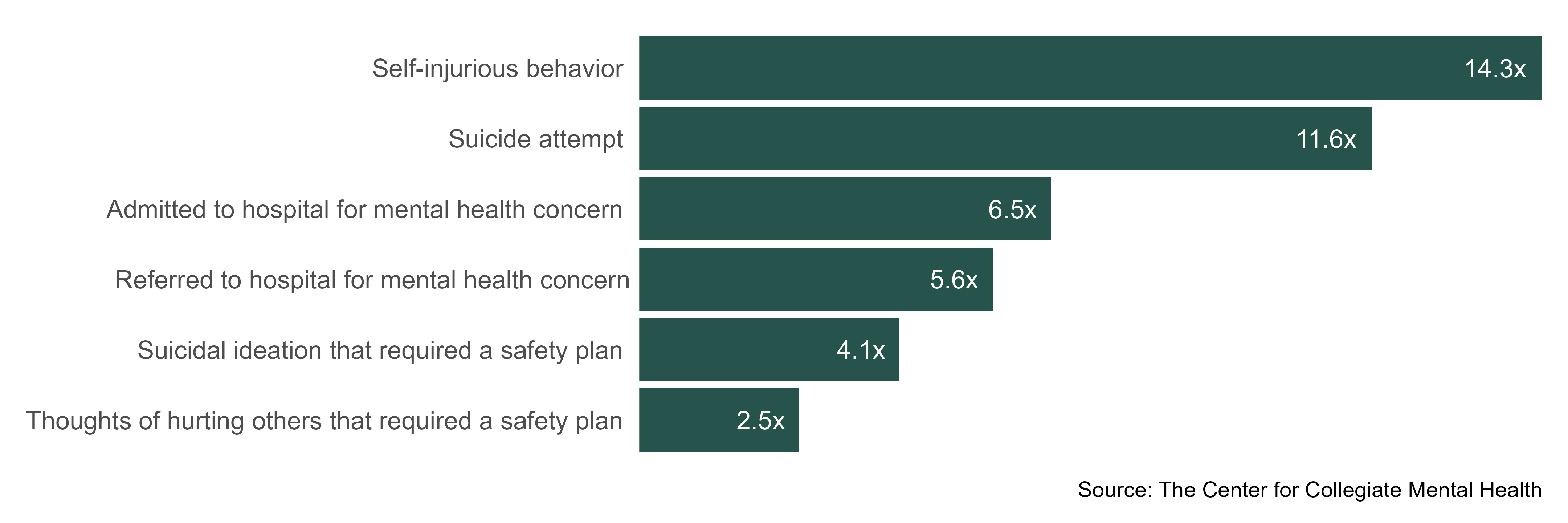

Students with S/SIB histories experienced substantially more critical case events during treatment than those without. The figure below displays how many times more likely students with S/SIB histories were to experience a particular critical event. The specific critical events shown below were chosen because of their established association with risk of harm to self or others.

Students with past S/SIB were 14.3 times more likely to engage in self-injury and 11.6 times more likely to attempt suicide during services. Additionally, they were 5.6 to 6.5 times more likely to be referred and admitted for hospitalization and 2.5 to 4.1 times more likely to need an active safety plan to manage their threat to themselves or others.

It is important to note that these critical events were uncommon in both students with and without past S/SIB. For example, approximately 1 in 180 (0.55%) students with S/SIB histories and 1 in 2,000 (0.05%) of those without attempted suicide during counseling services. Despite the low incidence rates, results show that students with S/SIB histories are disproportionately more likely to experience these events during treatment.

END OF TREATMENT

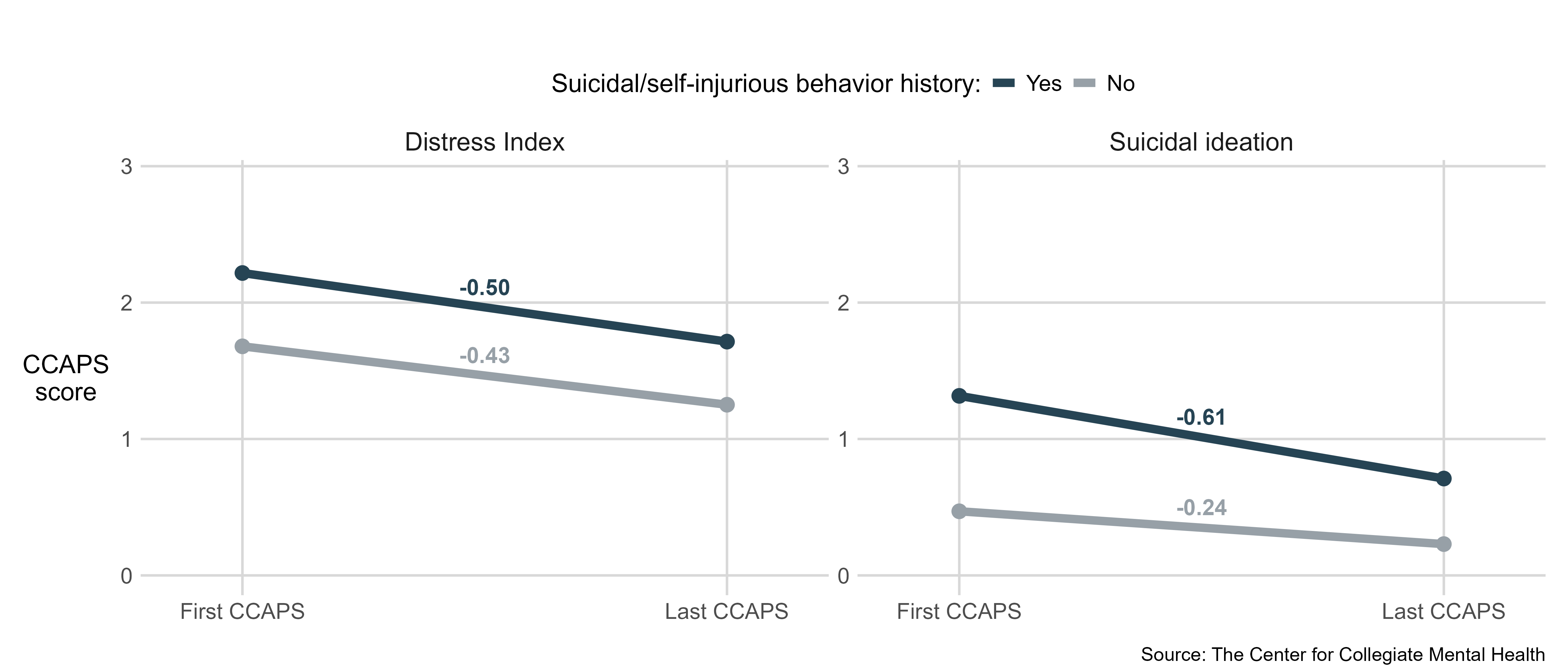

Improvement in general distress and suicidal ideation (i.e., change between first and last administrations of the CCAPS) were compared between students with and without past S/SIB. The changes were examined for all students, regardless of their level of symptoms at the beginning of treatment. The lines connecting first and last CCAPS administrations represent total improvement, where steeper lines indicate more change. The numbers above each line indicate the average raw change in symptoms for each type of distress.

Clients with S/SIB histories began treatment (first administration) with higher levels of general distress and suicidal thoughts than those without past S/SIB. Both groups showed similar rates of improvement in general distress symptoms during treatment. However, clients with past S/SIB demonstrated greater reductions comparatively in suicidal ideation during services. Despite demonstrable improvement on each outcome (general distress and suicidal thoughts), students with S/SIB histories, compared to those without, still ended services with considerably higher levels of symptoms.

SUMMARY

Findings

Suicide is a growing problem in the United States that has impacted college-aged individuals and motivated a robust implementation of prevention efforts on college campuses over the past two decades. As an indicator of success of these programs, more students have been initiating care at college counseling centers, particularly those with histories of suicidal/ self-injurious behavior (S/SIB), which are known prominent risk factors for suicide. As such, the current investigation examined the symptoms, presenting concerns, stressors and contextual factors, service utilization, and treatment outcomes of students who receive services with a S/SIB history.

The findings revealed that students with past S/SIB, compared to those without, began treatment with more severe symptoms of Depression, Generalized Anxiety, and overall distress symptoms. Clients with S/SIB histories were more likely to be assessed by clinicians as having current self-injury or suicidality, psychotic symptoms, mood instability, dissociation, gender identity concerns, violent thoughts or behaviors, and experiences of abuse/assault at the outset of treatment.

Additionally, students with past S/SIB utilized 1 more scheduled appointment or 15% more services, which included individual and group psychotherapy, case management, and psychiatric treatment. In terms of critical case events, students with S/SIB histories were 14 and 11 times more likely, respectively, to engage in self-harm and suicide attempts while receiving services at the counseling center. Finally, counseling center staff provided effective support to these students, as demonstrated by students’ substantial improvement in distress and suicidal ideation during treatment.

While these findings highlight that counseling centers play an essential role in providing care to students with suicide risk, these students still ended treatment with higher levels of distress and suicidal ideation. Given many counseling centers have shifted to short-term treatment models to manage demand/supply imbalances for services, these findings underscore the importance of preserving and fortifying the comprehensive, collaborative, specialized, and potentially longer-term care needed to effectively support students with elevated suicide risk.

Additional Considerations

It is important to note several considerations related to the current findings. The factors selected to define students with heightened risk of suicide included histories of suicidal/self-injurious behavior were based on prior research and theory emphasizing the salience of these variables. However, there are many other known risk factors for suicide among students receiving care at counseling centers (e.g., substance use, impulsivity, social isolation, access to lethal means). Thus, the group of students CCMH examined does not encompass the entirety of students in treatment at counseling centers who are at elevated suicide risk. Moreover, while 30% of students seen at counseling centers nationally reported a S/SIB history,

this percentage varied across individual centers: at the majority of centers, between 20% and 50% of students reported past S/SIB. Therefore, it is important for centers to examine their local data to determine how these findings might inform their services.

Additionally, although students with past suicidal/self-injurious behavior were more likely to engage in critical events during services (e.g., make a suicide attempt), these actions were uncommon for all students. As such, regardless of their history of S/SIB, a student is much more likely to not experience any critical events during their care at counseling centers.

Finally, the current findings underscored the enhanced needs for comprehensive services by students with elevated suicide risk, which especially included case management and psychiatric support. However, the actual amount of care at-risk students receive may be even higher than this examination was able to detect. For instance, clinicians often spend time outside of scheduled sessions consulting and collaborating with other providers, campus offices, and caregivers of students with acute or complex needs, which is not reflected in the number of sessions scheduled.

Furthermore, many counseling centers have neither case management nor psychiatric services available for a multitude of reasons, such as lack of financial resources or difficulty recruiting specialized providers. In fact, only 40.9% of centers nationally have a dedicated position to case management, and 38% of centers offer psychiatric care. Centers without dedicated case management or psychiatric providers are inevitably faced with formidable challenges, including having therapists conduct case management during counseling sessions without the assistance of a specialized case manager, coordinating with external providers for psychiatric care, or contracting with a service unaffiliated with the institution to provide these services. Consequently, many clinicians working at centers with a scarcity of these specialized services might become overburdened with managing multiple tasks in their finite amount of time with students, which could dilute the overall quality of care they provide. Therefore, it is imperative that colleges and universities invest in under-resourced counseling centers to ease the burden on counseling center staff and optimize treatment for students with heightened suicide risk.

Conclusions

The current findings highlight the critical role college counseling centers serve in supporting suicide prevention and campus safety initiatives within higher education, while concurrently identifying areas where potential gaps exist for under- resourced centers. A significant proportion (approximately 30%) of students treated at centers nationally are at elevated risk of dying by suicide, as defined by a history of suicide attempts or self-injurious behavior. Thus, it is imperative for colleges and universities to understand the gravity of mental health concerns and suicide risk among students receiving care at counseling centers and the unique and comprehensive service needs of this population. Given the majority of centers nationally lack the necessary resources to deliver comprehensive specialized services, institutions can support counseling center efforts to treat these at-risk students by investing in onsite psychological treatment, psychiatric care, and case management services, which enhances the capacity to collaborate with campus/external partners and provide longer- term care. These comprehensive services are a vital support system that is sometimes the only option for care available since many students with increased suicide risk might not meet criteria for treatment by external telehealth providers and vendors due to their S/SIB history. Despite these challenges, some institutions might need to creatively explore avenues to offer comprehensive services through a third-party provider. Regardless, investments in locally informed and collaborative counseling center care that includes adjunctive support services (e.g., Title IX, Dean of Students, Financial Aid, and Student Disability) are crucial to support this population, form campus/external partnerships, and achieve mental, emotional, and academic improvement for these students, which ultimately increases the likelihood of student success.

REFERENCES

Center for Collegiate Mental Health. (2016, January). 2015 Annual Report (Publication No. STA 15-108).

Center for Disease Control. (2024). Facts about suicide. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/index.html

Hayes, J. A., Petrovich, J., Janis, R. A., Yang, Y., Castonguay, L. G., & Locke, B. D. (2020). Suicide among college students in psychotherapy: Individual predictors and latent classes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 67(2), 104-114. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000384

The Healthy Minds Network. (2024, September). 2023-2024 National Data Report.

The JED Foundation. (2002). Fact sheet on college student suicide. Retrieved from The JED Foundation.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2021). Mental Health, Substance Use and Wellbeing in Higher Education.

Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Cukrowicz, K. C., Braithwaite, S., Selby, E. A., & Joiner Jr., T. E. (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117(2), 575-600.

Published 1/27/2025